Your Kid Is Trans. You Live in Texas. There Are No Good Options.

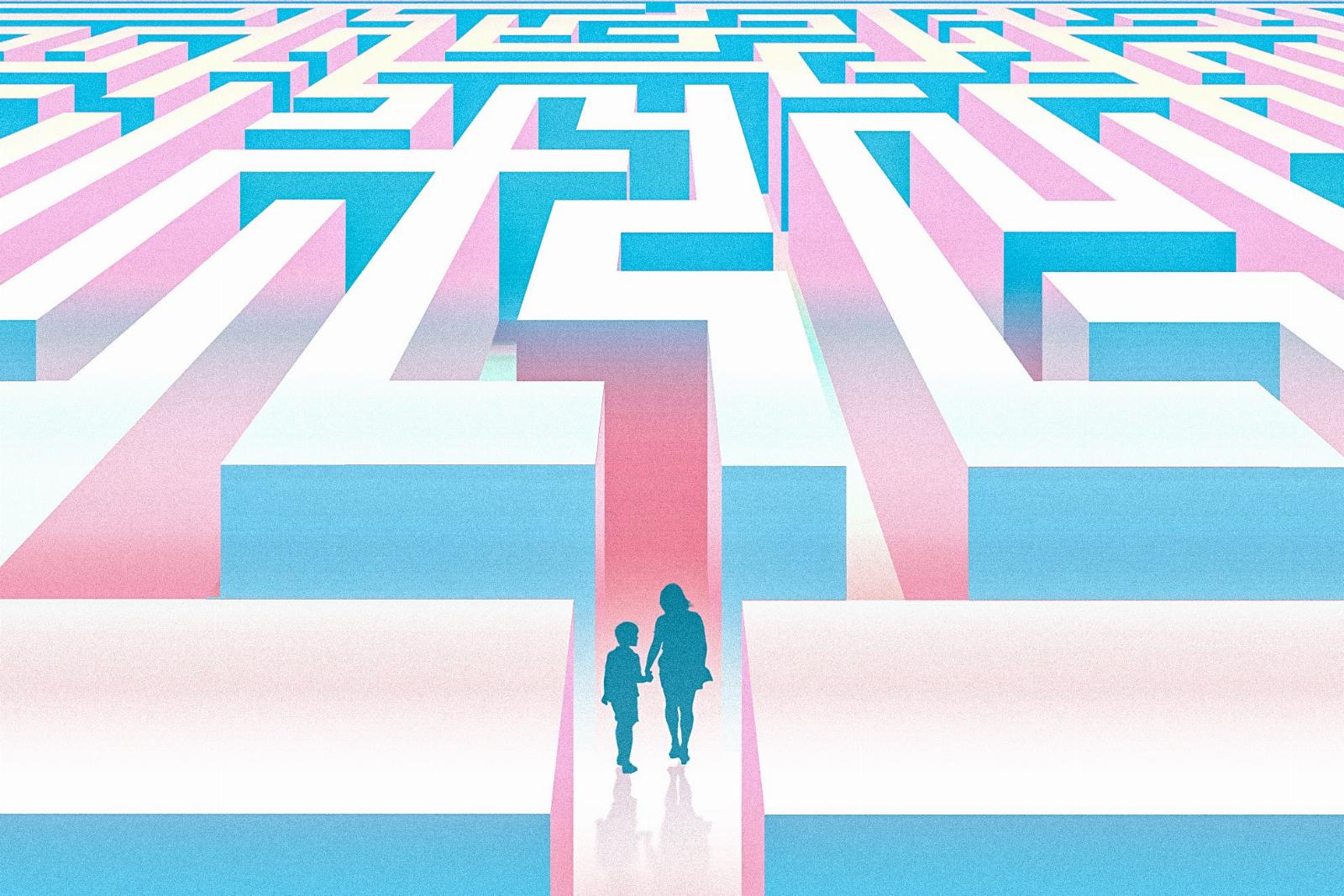

Reading Time: 13 minutesSudden bans on health care across the U.S. have left parents scrambling. It’s not as simple as just leaving for another state., Trans health care: How bans are forcing parents into a maze of choices.

Zeder was 7 when he told his parents that the body he’d been born into didn’t feel right for him. Since the age of 3, he had expressed distaste for traditionally feminine clothing and hairstyles. So when he asked his mom and dad to start calling him Zeder and using he/him pronouns, they weren’t surprised.

Zeder’s parents were eager to support him, but they didn’t know much about caring for a trans child. ‘I certainly didn’t have a village, or even one single human being that I knew to reach out to to say, like, Hey, can you help me know how to do the right thing, as a mom?‘ said Molli Lobo, Zeder’s mother.

With a referral from Zeder’s pediatrician, Lobo quickly sought guidance from Dell Children’s Medical Center, a highly respected institution in their hometown of Austin, Texas, that provides a wide range of health services for children and teens, including gender-affirming care. For nearly four years, Zeder saw a wonderful doctor there, at the adolescent medicine clinic. He didn’t yet need any medical interventions, but the doctor built a relationship with Zeder and provided information about what the family’s options would be as he neared puberty.

‘I felt like I was in good hands, as far as being sent in the right direction,’ Lobo said. She began connecting with other parents of trans kids to share resources and support.

Then, this May, when Zeder was 11, Lobo heard from a few of those other parents that Zeder’s doctor was no longer employed at the medical center. Neither were any of the other physicians who’d provided gender-affirming care at the adolescent medicine clinic. Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton had announced an investigation into the clinic’s provision of gender-affirming care, prompting the sudden departure of every doctor at the center who’d offered it.

At that point, gender-affirming care for trans adolescents was still legal in the state. But Paxton had used his power to try to intimidate providers into ending that legal care, as part of the state’s concerted assault on health care for trans youth. It worked.

Zeder’s parents were devastated. Their child had a long-standing relationship with a doctor who made him feel comfortable. They had plans to start Zeder on puberty blockers, medication that safely and reversibly delays the bodily changes of puberty to prevent distress among trans and gender-nonconforming adolescents. Now Zeder’s future looked uncertain.

Zeder is one of thousands of kids and teens throughout the U.S. who are suffering the effects of a targeted attack on one of the most vulnerable and marginalized groups in the country. Their parents are now faced with a choice: If they want their children to have access to essential, physician-recommended medical care, they must uproot their lives or plot out a series of convoluted steps to access care across state lines.

In the midst of this GOP-manufactured crisis, advocates are trying to find ways to mitigate the damage. In some cases, they’re looking to the map that has been sketched out by activists to help pregnant people get abortions, another form of vital health care that has been abruptly restricted in recent years. But it’s becoming clear that the restrictions on trans health care are creating a maze unto itself.

Soon after Zeder’s doctor left, the Texas governor signed a ban on all gender-affirming medical treatments for transgender minors. The news ‘took my breath away,’ Lobo said. ‘It was like this automatic Oh my God. This is not something that we’re going to be able to navigate easily.’

In the past three years alone, life as a young transgender person in the U.S. has changed dramatically. Before 2021, gender-affirming medical care was legal in all 50 states. None had even tried to ban it. Today, 22 states have passed restrictions on that care—and while several have been blocked in court or have yet to take effect, most are active law.

Treatment plans for trans minors are as unique as the teens themselves. But usually, if medically indicated for the patient, treatment starts with puberty blockers for young adolescents and sometimes progresses to hormone therapy (testosterone or estrogen) for older teens. Surgery is uncommon for trans youth, though some older teens with enduring gender dysphoria opt for chest surgery.

Health experts agree that gender-affirming medical care is an essential tool in treating gender dysphoria and helping trans youth live happy, healthy, well-adjusted lives. Dozens of medical groups—including the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Medical Association, and the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine—have issued statements recognizing the necessity of access to that evidence-based, time-tested care.

Some of the new laws ban gender-affirming care for all trans minors. Others allow youth who are already receiving care to be legacied in and continue their treatment, while banning new patients from initiating care. Many contain harsh penalties, such as felony charges, for providers who offer the treatments.

This fast-changing landscape has plunged families like Zeder’s into chaos, as parents attempt to keep track of laws, find new medical providers, and map out a future in which their trans children can thrive. News reports are filled with stories of families who have uprooted their lives and moved to friendlier states to protect their trans kids from laws that prevent them from participating in sports, using the appropriate restroom, and getting recommended medical care.

But families who move across state lines are the exception, said Jasmine Beach-Ferrara, executive director of the Campaign for Southern Equality, an organization that supports LGBTQ+ people in the Southern U.S. The vast majority of families with trans kids that CSE serves have no plans to relocate. Moving requires money, finding a new home (and often a new job), and a willingness to give up what may be a cherished, generations-old community. That’s a tough ask for many parents, especially if there are other children in the picture.

Early this year, CSE launched a program to help young people living in states that have banned gender-affirming care find new providers in states where it remains legal. The Southern Trans Youth Emergency Project connects families in the South with health care facilities that are currently taking new patients—usually in the closest possible state with access, or in a state where a loved one lives—and provides $500 grants to offset expenses. So far, the program has distributed more than $300,000 to about 600 people and families. The organization has also begun offering a second round of grants to families in the program, since gender-affirming care requires regular appointments.

‘Our mindset is very much like the mindset you’d have in the wake of a hurricane hitting the coast,’ Beach-Ferrara said. ‘This is a crisis. And it’s a crisis we can respond to.’

The project bears similarities to the abortion funds and practical support networks that have helped a growing number of patients find abortion providers, cover travel costs, and pay for abortion care following the overturning of Roe v. Wade. In both cases, a right-wing policy agenda has cut off access to essential, lifesaving medical care in roughly half the country, forcing patients to forgo that care or travel long distances at great expense. (Patients seeking abortions can also order medication in the mail, though that poses the risk of possible legal trouble.) Some patients in states with abortion bans have been able to get care under this system: In the year after Roe was overturned, as legal abortions all but ended in states with bans, rates increased elsewhere due to an influx of out-of-state patients and loosened restrictions that improved access in blue states. But an untold number of people have been successfully barred from terminating their pregnancies and forced to birth children against their will.

There are important differences between abortion care and gender-affirming care, however. Getting abortion medication or an in-clinic procedure does not require ongoing care; usually, patients have to make only one trip. That’s not the case for gender-affirming care, which, like most long-term medical treatments, necessitates consistent check-ins on a patient’s physical and mental health, in addition to periodic prescription refills. Even if a patient’s family is able to work out the finances and logistics for one trip out of state, they’ll need to make another trip in three to six months—and another several months later, and so on. Emergency measures are not sufficient here. Families must find a sustainable long-term solution.

As it stands, the nation’s patchwork system of laws requires trans and gender-nonconforming youth in broad swaths of the country to go to absurd lengths to fill their prescriptions. The medications they need can be prescribed in a video telehealth appointment, but at the time of the appointment, the patient must be physically located in a state where the treatment is legal, and they can get the medication only from a pharmacy in one of those states.

One trans teenager from Mississippi who found a telehealth provider through CSE had to drive with his mother to Alabama, dial into his appointment from a cellphone in the parking lot of a country store, and pick up his medication at an Alabama Walgreens before driving 200 miles home. (Alabama has passed a ban on gender-affirming care for minors, but a judge has temporarily blocked part of it.)

And the reality on the ground for families scrambling to find care is often even worse than the letter of the law would dictate. Jennifer Abbott, a physician in North Carolina, recently prescribed a testosterone refill to a teen patient, an action that was legal under the state’s ban. (Her patient had been exempted from the ban because he’d started his care before it took effect.) After the patient took the prescription to a chain pharmacy, Abbott’s clinic got a call from the pharmacist who received it.

‘This pharmacist said to my colleague, ‘This is illegal. This prescription is illegal,’ ‘ Abbott said. ‘That’s just misinterpretation on the part of the pharmacist. And to call up in an angry way and kind of be whistleblowing when it’s not illegal—I mean, that’s really upsetting to me.’

The pharmacist refused to fill the patient’s prescription and informed the patient’s family that no other pharmacy in the chain would fill it either.

Alex Dworak, a physician in Nebraska, said his patients have encountered similar barriers in the state. Gender-affirming care is still legal in Nebraska for minors who had already begun their care before the new restrictions took effect, as well as for new patients who meet a set of strict requirements, such as a mandatory 40 hours of ‘gender-identity-focused‘ therapy that is ‘clinically neutral and not in a gender-affirming or conversion context.’

So-called gender-exploratory therapy is sometimes promoted by conservatives as a middle ground between conversion therapy and affirming therapy. But it still holds that kids who say they’re trans are often just gay or autistic, and that medical treatments should be a last resort. ‘Saying it can’t be affirmative is kind of—I mean, that’s de facto conversion therapy,’ Dworak said.

And even with the legal exception for existing patients, Dworak has heard from colleagues who have had to try to persuade reluctant pharmacists to fill legal prescriptions.

‘Youth already on treatment were supposed to be grandfathered in—there have been interruptions there,’ Dworak said. ‘And this is what the proponents have been saying, quite out loud, that they don’t want any of this care to happen.’ Other doctors who care for transgender adults and cisgender women who need estrogen for fertility treatments have told Dworak that their patients are having prescriptions rejected too.

Some physicians are also refusing to provide legal care. In states that have passed a ban but currently permit gender-affirming care for minors—because a ban has yet to take effect, has been blocked by a judge, or exempts existing patients—many providers have stopped seeing trans youth or will not take on new patients for fear of lawsuits, harassment, or malicious inquiries from right-wing politicians.

In Missouri, the ban on gender-affirming medical care for youth allows those who are already actively receiving care to continue their treatment. But multiple major clinics—including health centers run by Washington University in St. Louis and the University of Missouri—have stopped seeing existing patients and canceled their ongoing prescriptions for puberty blockers and hormones. Their reason? The ‘unsustainable liability‘ created by a provision of Missouri’s ban that would allow people who received gender-affirming care as minors to sue their doctors until up to 15 years after the treatment or their 21st birthday, whichever is later. (Usually, Missouri patients have just two years to bring a medical malpractice suit against a provider.)

‘Everyone is having to do risk assessment and risk mitigation,’ Beach-Ferrara said. ‘What we’re seeing, basically, is that risk analysis for some providers is saying there’s just too much risk involved, even if they can legally and permissibly provide this service.’

There are echoes here of the chaos wrought by abortion bans. In recent years, out of an abundance of caution, multiple Planned Parenthood locations stopped providing legal abortions before state bans went into effect. And pharmacists began refusing prescriptions for drugs that treat cancer, lupus, ectopic pregnancies, and stomach ulcers, just because they can also be used to induce abortions. (It’s worth noting, however, that Planned Parenthood clinics in Missouri are continuing to serve their existing patients who are trans minors.)

This chilling effect was no unintentional side effect of abortion bans, and it is not an incidental upshot of bans on gender-affirming care either. It is an essential part of the GOP’s assault on health care for women and LGBTQ+ people. Right-wing advocates are counting on the fear of violence and ballooning legal expenses among risk-averse medical providers to amplify the impact of their laws beyond what is written on the page. And they intend to create an atmosphere of confusion and mayhem, such that it’s harder for patients to know what care they can legally access in their home states.

When Molli Lobo found out this spring that Zeder’s Austin clinic was no longer offering gender-affirming care, she panicked. But because the Texas ban would not take effect until September, Lobo thought she had a few months to get Zeder started on puberty blockers before she’d need to find a new provider out of state. (The medication is delivered via injections that can last from one to six months, or an implant that lasts about a year.) Lobo drove to Houston to visit a clinic that was still providing gender-affirming care.

The clinic turned her away. Even though the care Zeder needed was legal, Lobo said, she was told that it would be too risky for the clinic to take on a new patient because it wouldn’t be able to give him follow-up care after the ban took effect.

Instead, the clinic said, Lobo could contact the Campaign for Southern Equality for help. She did, and CSE put her in touch with Elevated Access, a nonprofit that arranges free private flights from volunteer pilots for people who can’t get an abortion or gender-affirming care close to home.

Elevated Access scheduled a trip for Zeder and Lobo to fly to Albuquerque, New Mexico, where Zeder had an appointment at a clinic. Then, a couple of weeks before the flight, the clinic canceled the appointment, citing legal and logistical concerns with providing care to an out-of-state patient who couldn’t use his health insurance.

‘It was frustrating. It was hard to really understand—it caught us off guard,’ Lobo said. ‘It was just like going back to the very beginning. We thought we had it squared away the whole time, but we did not.’

Now Lobo isn’t sure what they’ll do. Her Texas-based insurance will not cover the care Zeder needs. Without it, even if she and Zeder can make several trips to see a provider out of state—the New Mexico clinic has since said that it may be able to offer care after all—she has been told that the medication will cost $10,000 per year out of pocket. Lobo and her husband have lived in Texas for 18 years, and they don’t want to move. Their other child is still in high school, and they don’t want to take him out before he finishes. ‘Having to stay here is unfair for the younger one. Having to leave is unfair for the older one,’ Lobo said. The current plan is to relocate to Oregon after their older son graduates in a couple of years.

Another parent of a trans child in Lobo’s community told her that they plan to try a convoluted plot to game the system: Get a remote job based in a state where gender-affirming care for adolescents is legal, pretend to live in that state by using the address of a loved one who actually lives there, get health insurance in that state, and visit that state periodically for medical care.

The scheme sounds complicated and difficult to pull off. But if you’re the parent of a trans child in a state that bans gender-affirming care, few of the options at your disposal are simple, and none of them are good. You can pack up your family and move to a new state; rely on grants or a free plane ride and take time off from work to make multiple trips across state lines each year (with hundreds of dollars on hand to pay for care out of pocket); or, maybe, execute an elaborate remote-work scheme that might not ultimately pan out.

And even families who are able to make it across state lines for gender-affirming care may face lengthy waiting periods before they can be seen. ‘We’re really seeing providers being strapped in terms of their capacity. You know, there aren’t a huge number of providers who offer this care, because there just aren’t that many trans people,’ said Kellan Baker, executive director of the Whitman-Walker Institute, a Washington-based research and advocacy organization focused on LGBTQ+ health.

The institute oversees a coalition of more than 500 gender-affirming care providers from across the country who are working together to chart a path forward for their specialty in this moment of crisis. The group is working with providers in states without bans to figure out how to make their care more affordable for new patients coming from out of state. Once a ban has passed in a state, the coalition helps providers direct patients to mutual aid funds and organizations like CSE that are providing financial assistance to, as Baker put it, ‘defray the cost of becoming a medical refugee.’

These efforts will ease some of the difficulties families with trans children currently face in much of the country. But there is no doubt that the state bans will still succeed in doing exactly what their supporters intended: depriving thousands of trans young people of the care they need to feel comfortable and safe in their own skin.

‘What’s actually happening is a really cruel science experiment, where trans kids who are happy and healthy—under the care of their doctors, with the support of their parents—are now being forcibly taken off their medication, which is absolutely medically contraindicated,’ Baker said. ‘And we know it’s going to hurt them. And so the effect of this experiment seems to be: Just how badly will we hurt them?’

Before the Texas ban on gender-affirming care for trans youth was signed into law this past June, Zeder’s parents thought they were ahead of the game. Many other trans teens aren’t able to access care until puberty has already caused permanent changes to their bodies. Sometimes, they don’t come to understand themselves as transgender until adolescence; in other cases, legislative bans, financial barriers, or a lack of parental support closes off avenues to care. Unlike those teens, Zeder would have been able to delay puberty at its onset, forestalling those changes that might cause him dysphoria. Then, later in his teens, he might have started hormone therapy to undergo male puberty.

But Zeder’s care was interrupted right as he was about to turn 12. Now he has started puberty, and he still doesn’t have the medication he needs to pause it. ‘The things that we were hoping to avoid for him to feel comfortable in his body—those are now out the window,’ Lobo said. ‘We missed the mark because all this happened. It’s just so sad.’

A few years ago, when Zeder first began living under his new name and pronouns, Lobo noticed a slight change in his demeanor. He was the same kid he always had been, but he was sillier at times, visibly more at ease with himself. Lobo desperately wants to protect that precious part of her child.

‘What a bright light and what a beautiful thing for this child to have this awareness,’ she said. ‘I think there’s a lot of folks in the world who really, truly believe these children do not have a clue what’s going on inside of themselves. And I absolutely disagree.’

Lately, Beach-Ferrara and her colleagues at the Campaign for Southern Equality have been mapping out hypothetical scenarios for 2024 and beyond. If Republicans control the White House and both houses of Congress after next year’s election, it would pave the way for a national ban on gender-affirming care for minors—and adults.

‘We might have to think creatively about international care, about international waters,’ Beach-Ferrara said. ‘Every option is on the table as we think about: How do you help people get the health care that they need and deserve? And how do we navigate a climate in which increasingly authoritarian laws are being passed to infringe on people’s fundamental freedoms?’

In the midst of that grim climate, CSE is attempting to find space for hope. The organization has collected hundreds of messages for Southern trans youth from supporters and is disseminating them in a booklet to families who receive grants. On some of the pages, trans adults tell their own stories of hardship and survival. Others are filled with encouragement from strangers around the world: ‘You are the magic we need in this world.’ ‘You are the FUTURE. You know yourself better than anybody else.’ ‘No matter what anyone tries to tell you, you ARE being fought for.’

Over the past several years, Beach-Ferrara has witnessed an increase in young people coming out as trans in the South. And she’s seen concurrent growth in the support they receive when they do: More families are celebrating them, more schools are affirming them, more therapists are versed in the needs of trans youth, and more pediatricians are prepared to offer competent care. Those things will continue to have an impact on the well-being of trans kids and teens, even as ‘Don’t Say Gay’ laws and bans on medical care restrict certain kinds of support.

‘These laws are not detransitioning kids. They don’t have the power to do that,’ Beach-Ferrara said. ‘Nor do they have the power to create a sort of scorched-earth environment where all the support that has been built over decades—and is very, very real and powerful—goes away.’

Ref: slate

MediaDownloader.net -> Free Online Video Downloader, Download Any Video From YouTube, VK, Vimeo, Twitter, Twitch, Tumblr, Tiktok, Telegram, TED, Streamable, Soundcloud, Snapchat, Share, Rumble, Reddit, PuhuTV, Pinterest, Periscope, Ok.ru, MxTakatak, Mixcloud, Mashable, LinkedIn, Likee, Kwai, Izlesene, Instagram, Imgur, IMDB, Ifunny, Gaana, Flickr, Febspot, Facebook, ESPN, Douyin, Dailymotion, Buzzfeed, BluTV, Blogger, Bitchute, Bilibili, Bandcamp, Akıllı, 9GAG