We’ve Been Asking the Same Question About Prison Tech Training for 50 Years

Reading Time: 6 minutesLearn-to-Code Programs in Prison Train People for the Future. Many of the Officials Approving Them Are Stuck in the Past., Many prison officials were more supportive of coding programs in the 1970s than they are today., Why prison tech training is stuck in

This story is published in partnership with Open Campus, a nonprofit newsroom focused on higher education. Subscribe to College Inside, an Open Campus newsletter on the future of postsecondary education in prison.

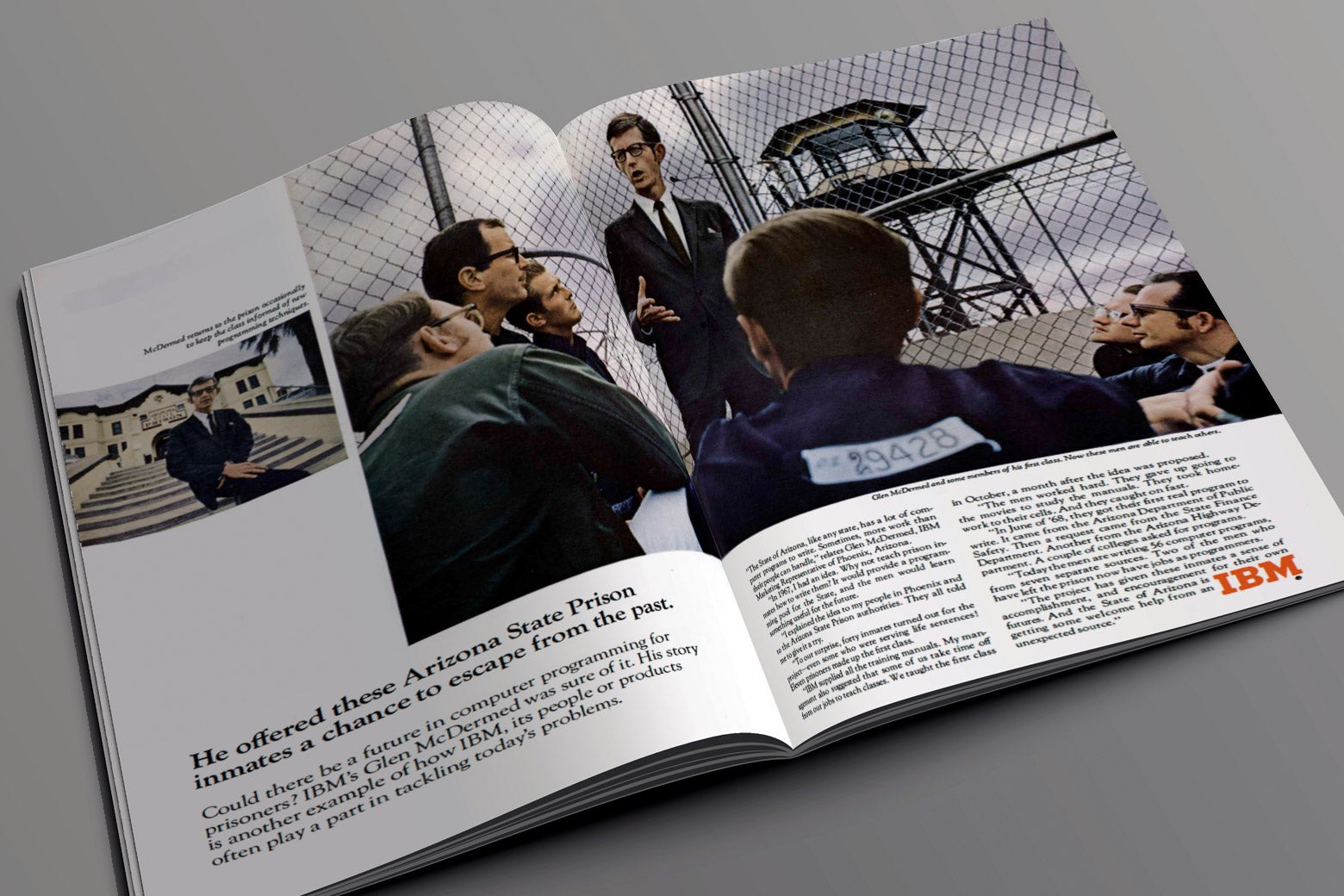

A slight man wearing horn-rimmed glasses and a suit with a pocket square gestures as he stands before a group of men in blue jumpsuits. They listen attentively. A guard tower and chain link fence loom in the background. ‘He offered these Arizona State Prison inmates a chance to escape from the past,’ the text below the photo reads. ‘Could there be a future in computer programming for prisoners?’

The photo is from an ad in Scientific American that’s more than 50 years old. Yes, 50 years. Not much has changed in conversations about prisons, education, and technology since then.

The benefits of tech training in prison were already known in 1970. People are less likely to return to prison if they have marketable skills that lead to jobs in high-demand fields with livable wages. But despite the promise of such programs, the pitfalls also remain the same: They can be costly; they can be difficult to scale; and they are subject to the whims of tech-averse prison officials.

While the pandemic helped make technology like tablets more common in prison, perceived security risks often trump opportunities for learning and rehabilitation. And as much as technological advances have allowed more wide-scale access to tablets (some of which come with high fees), they can just as easily be taken away.

The slender man in the ad photo is Glen McDermed, a marketing executive from IBM. In 1967, he proposed training incarcerated men to program computers to meet growing industry demand as tech companies began jumping on the information processing bandwagon. ‘The men would learn something useful for the future,’ McDermed said of the program in a quote accompanying the ad. IBM employees taught the initial classes to 11 men. Long-term prisoners eventually took over training to make the program self-sustaining. The program offered the men ‘real-world’ experience that saved Arizona millions of dollars in lucrative contracts between corrections and other state agencies, according to a 1970 cover story for Computerworld.

Similar programs were launched elsewhere, including Oklahoma and New York. A 1967 story in the New York Times described a $1,200 computer course offered to incarcerated men for free. ‘The cells may be narrow, but the intellectual horizons are growing wider at Sing Sing,’ McCandlish Phillips wrote. The spokesperson for the institute offering the course told the Times that the men could learn programming without ever needing to touch a computer. At the time, code was handwritten until it was transferred onto a ‘keypunch card,’ which was then fed into a mainframe computer.

In Massachusetts, more than 1,000 men were trained as programmers at Walpole correctional facility over the 1970s. The program there, sponsored by Honeywell, started the same year as the IBM program after a prisoner saw a newspaper want-ad for data processors.

But these training programs were sometimes short-lived, despite the benefit to individuals. William Short spent five years working seven days a week—at $3 a day—as a computer programmer at a maximum security prison in Somers, Connecticut. When he was released in 1975, he quickly found employment at an insurance company earning $13,400 a year (approximately $77,000 today). In a newspaper interview at the time, he said that learning a vocation in prison helps a man come out ‘with a whole frame of mind that is better than what he went in with.’ However, not long after Short was released, the program that had given him such marketable skills was no more. It had been shut down due to difficulties retaining an instructor, high costs, and staff resistance, the corrections commissioner told the newspaper.

By 1978, IBM’s program suffered a similar fate. A new warden had phased out most of the educational programs at the Arizona State Prison, the prison newspaper reported, because he ‘didn’t understand them,’ as one man put it. ‘Under the guise of his security program, he put a stifle to the various programs around here.’

In 2023, the benefits from tech training in prison remain much the same. One big difference? Keypunch coding has been replaced by cloud computing and javascript. In 2022, the D.C. Jail launched an Amazon Web Services cloud certification in collaboration with APDS, an education technology company that provides tablets to people in prison, at no charge to the students.

Being able to provide the training on the APDS tablets was significant because ‘it’s really hard to provide any kind of STEM programming inside that leads to some sort of industry certification or a living-wage job afterward,’ said Amy Lopez, former deputy director for the D.C. Department of Corrections. Out of the 21 men who started the program, 11 completed the training. Most of those who didn’t finish chose to drop out or were transferred out of the jail, said Arti Finn, APSD cofounder and chief business development officer. The remaining men were able to take the high-stakes test to earn the Amazon credential inside the D.C. Jail, which was already set up to provide secure exams such as the GED.

Leonard Bishop, who participated in the program, hadn’t touched technology in the 17 years he served in the federal system prior to transferring to the D.C. Jail in 2018. When he first got a tablet, he said it took him a few days to figure out how to navigate through it, but then ‘I couldn’t put it down.’ Bishop said he was surprised by how easy it was to learn the skills he needed to earn the AWS certification. He said he looks at it as a career opportunity, rather than ‘just’ a job. ‘It helps you transition back into society, especially for someone who has been gone so long,’ he said. The average annual pay for an entry-level AWS cloud practitioner position is almost $90,000, according to ZipRecruiter.

The pilot program at the D.C. Jail supplemented the tablet-based curriculum with face-to-face instruction by Amazon employees and other experts and incorporated opportunities to practice job skills such as interviewing. But the hope is that the AWS curriculum, and other industry certifications, can be scaled to allow people to self-study for the certification on the APDS tablets, Finn said. It also increases access for people who aren’t able to take part in face-to-face classes due to schedule conflicts, such as with their prison job.

When APDS started talking with Amazon, one of the goals was to reach the large number of people who sit behind bars without any access to any kind of programming, Finn added. The tablets are also equipped with video communication and messaging services, and could be used to offer online apprenticeships that create additional opportunities for hands-on learning.

Still, some are skeptical that tablet-based training alone will tranMediaDownloader into high-paying jobs. It’s difficult to learn on a tablet, said Jessica Hicklin, who taught herself to code in prison. She’s now the chief technology officer of Unlocked Labs, a Missouri-based nonprofit that trains incarcerated software developers. Unlocked Labs is trying to add the Amazon cloud certification to its own training platform because the underlying knowledge is useful. But, Hicklin said, it would be difficult to break into the tech industry without direct connections to companies that engage in second-chance hiring. ‘I’m not sure it overcomes the stigma’ of having a record, she said.

There are other criticisms of tablets, too. APDS has committed to never charging incarcerated people for its content or services. (Corrections departments or other state agencies pay for their tablets, Finn said). But other technology vendors routinely charge exorbitant prices for communications services and entertainment content. Critics also argue that they provide surveillance creep, creating more opportunities for corrections officials to monitor people in prison.

And with the prospect of higher education becoming more widely available in prison with the restoration of federal financial aid later this year, those companies are also trying to rebrand themselves as educational providers. The two largest tablet providers, Securus and ViaPath Technologies (formerly GTL), together supply more than 1 million tablets to U.S. prisons. That means around half of people in prisons currently have some kind of tablet access. Just like in 1970, access to beneficial programs remains contingent upon supportive prison administrators. In fact, many incarcerated students are reluctant to criticize online learning opportunities out of fear they will be taken away.

Five years ago, for instance, Colorado became one of the first states to roll out tablets, which included educational programming, to around half of its prison population. But months later, prison authorities confiscated them. (The Colorado Department of Corrections did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

Today, most people in Colorado prisons still don’t have tablets. And across the country, the question posed in the IBM ad back in 1970—’Could there be a future in computer programming for prisoners?’—remains unanswered.

Ref: slate

MediaDownloader.net -> Free Online Video Downloader, Download Any Video From YouTube, VK, Vimeo, Twitter, Twitch, Tumblr, Tiktok, Telegram, TED, Streamable, Soundcloud, Snapchat, Share, Rumble, Reddit, PuhuTV, Pinterest, Periscope, Ok.ru, MxTakatak, Mixcloud, Mashable, LinkedIn, Likee, Kwai, Izlesene, Instagram, Imgur, IMDB, Ifunny, Gaana, Flickr, Febspot, Facebook, ESPN, Douyin, Dailymotion, Buzzfeed, BluTV, Blogger, Bitchute, Bilibili, Bandcamp, Akıllı, 9GAG