The Race to Carve Up the Moon

Reading Time: 5 minutesThe commercialization of space is here. International law isn’t prepared., Space law: The commercialization of space is here. International law isn’t prepared.

As human access to space expands, the influx of new actors promises to forever alter the dynamics of space. The head-to-head U.S.–Soviet rivalry that once dominated the Space Race will evolve into something more inclusive—but also messier. Aspiring space nations, such as Luxembourg, India, and China, together with new categories of nonstate actors, including large industrial players, startups, and universities, raise questions about how we should regulate space. Explosive commercialization is particularly challenging for existing space law, whose foundations were set in the 1960s and designed with national governments in mind.

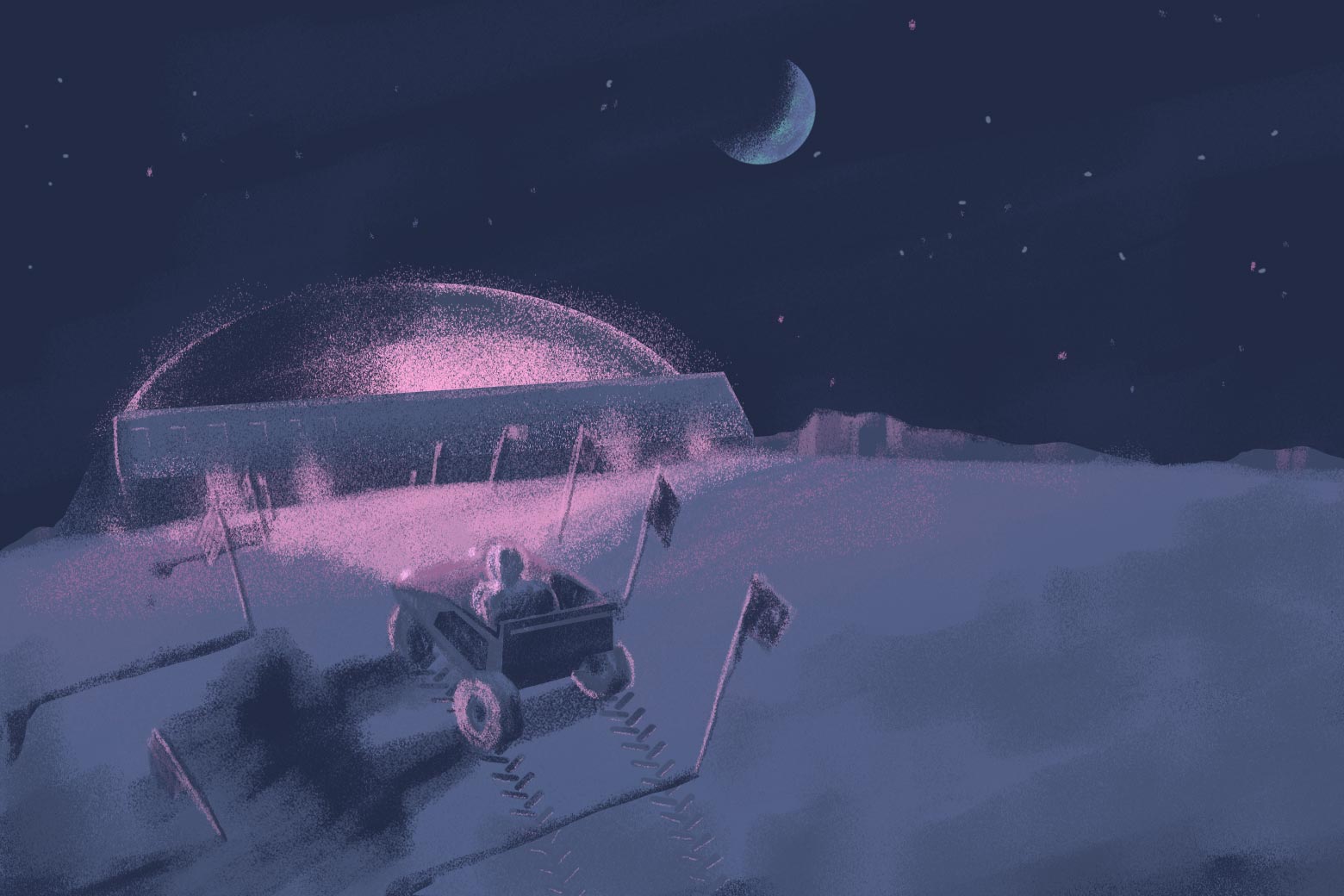

This rapidly changing environment is dramatized in ‘Little Assistance,’ a new Future Tense Fiction story from Stephen Harrison. The story follows the first judge in space, who is considering a case that highlights how public–private collaborations and commercialization are testing existing national and international space laws.

The story propels us into the future, where NASA has contracted with the corporation Stellarco to run its Luna Homestead ‘settlement’—a claustrophobic off-Earth mining town. Stellarco files suit against NASA when its drill is damaged after hitting a pocket of hardened lunar bedrock. Who should be responsible for the cost of repairing the drill, and the time and money lost during the process of repair? Commercial mining is an underdeveloped aspect of international space law, and as someone who researches the future of property rights in space, I often turn to science fiction like ‘Little Assistance‘ to fill in the gaps of what we can expect.

Since the dawn of the Space Race, science fiction writers have been dramatizing the legal and political dimensions of space exploration. For example, in 1961’s Stranger in a Strange Land, Robert Heinlein describes a fictional court decision that establishes that the moon is owned by those who reside on it. Stories like Heinlein’s and Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars trilogy (1992–1996) illustrate the limitations of existing space law, which largely excludes corporations and other nonstate actors, concentrating instead on protecting state sovereignty and preventing state conflict over territory and resources. This creates ambiguity around commercial actors like the fictional Stellarco, especially when they are functioning in partnership with governments. And this ambiguity is where speculative fiction can be a useful tool: How can we better align regulation with the actual activities humans will be undertaking in space? How can governments and private enterprise maneuver around one another, sharing jurisdiction on the moon and beyond?

To understand how we ended up with our current governance regime for outer space, it’s worth looking back to the 1957 Sputnik launch. The Soviets’ successful launch made space regulation urgent in order to avoid the escalation of weaponization between the U.S. and the Soviet Union in space. During the Cold War, negotiations started at the United Nations, and in 1963, the U.N. General Assembly adopted the Declaration of Legal Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space. Subsequently, the U.N. Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space penned five international treaties and five sets of principles, which were ratified by 114 countries. The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 was the most wide-ranging and influential.

These treaties deal with lots of sticky issues: non-appropriation of space by any one country, arms control, freedom of exploration, liability for damage caused by human-created objects, safety and rescue of spacecraft and astronauts, prevention of harmful interference with space activities and the environment, notification and registration of activities, scientific investigation, exploitation of natural resources, and settlement of disputes. Dispute resolution is at the center of Harrison’s story, which illustrates how enforcing the principles of the Outer Space Treaty becomes more challenging when space and its resources are opened to commercial activities. The arrival of new actors like SpaceX has put pressure on states to update their legal and political frameworks.

Responding to the commercialization of space—and, perhaps, seeking to take the lead in a new kind of space race—the U.S., Luxembourg, the United Arab Emirates, and Japan have adopted laws that allow commercial mining. They assert that private mining activities comply with Article II of the Outer Space Treaty, which stipulates that ‘outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use, or by any other means.’

Not all space lawyers agree with this interpretation: These national laws are controversial, with some experts claiming that they violate the spirit, if not the letter, of the Outer Space Treaty. As the preamble to the treaty states, the exploration and use of outer space should be for peaceful purposes and ‘for the benefit of all peoples irrespective of the degree of their economic or scientific development.’ For a small number of wealthy nations to allow exclusive property rights over commercially mined resources muddles the idea that space should be for the common good.

‘Little Assistance‘ highlights another often-overlooked aspect of the debate over the future of space exploration by representing Stellarco’s legal dispute with NASA as a matter decided by the U.S. federal court system. Although the Outer Space Treaty bars states from claiming sovereignty over the moon or any other celestial bodies, this doesn’t mean that commercial entities like SpaceX operate without regulatory oversight.

The treaty requires states to authorize and supervise the activities of nongovernmental entities. The U.S., like other spacefaring nations, exercises jurisdictional authority over its own registered space entities, including government agencies, private companies, and individuals involved in space exploration or commercial endeavours, in accordance with both national and international space law. In this way, even private-sector activities in space can have the effect of extending a nation’s power by establishing zones of governance and oversight off Earth.

U.S.-registered space companies operate under the oversight of U.S. federal agencies—primarily the Federal Aviation Administration and the Federal Communications Commission. These agencies grant licenses and permits for space activities, regulate radiofrequency spectrum use, and ensure compliance with U.S. laws and regulations. This means the U.S. government has a responsibility to ensure that private companies’ mining activities align with the obligations set forth in U.N. space treaties.

In other words, although the influence of the commercial space sector will certainly expand over the coming decades, as Harrison’s story illustrates, corporations do not yet have the power to dictate a new set of extraterrestrial laws. This is where the law and science fiction stories depart. While Heinlein, Robinson, and other sci-fi authors imagine space enterprises and communities declaring their independence from earthly powers, the contours of international law are still being drawn by nation-states.

But in contrast to the early movements of space law in the 1960s, the main platform for policymaking may no longer be the U.N. In 2020, NASA, in coordination with the U.S. Department of State and seven other founding nations, established the Artemis Accords, currently signed by 29 countries. Like in ‘Little Assistance,’ these accords indicate that national governments may tighten their grip on the moon and other celestial bodies, rather than losing ground to emerging private-sector firms.

The Artemis Accords propose strengthening and extending territorial jurisdictions through ‘safety zones.’ In theory, these zones give states operating on a piece of lunar land the power to exclude other states and their nationals from accessing the zone, and to enforce the laws of the state operating the zone.

Although to what extent this equates to expanding territory and asserting sovereignty is debatable, claiming a piece of lunar real estate as a safety zone comes close to national appropriation, even if there isn’t a formal claim of ownership. In ‘Little Assistance,’ Stellarco’s Luna Homestead may not represent a formal U.S. territory, but it flies the U.S. flag (alongside the corporation’s banner), and legal disputes unfolding on that land are governed by U.S. law, subject to U.S. federal jurisprudence.

These multilateral agreements, in tandem with national laws that help to expand the commercial space sector, could enable nations and their commercial partners to carve up the moon and other space arenas into exclusive zones—setting the stage for another high-stakes geopolitical game of space chess. If we value the ideals of the Outer Space Treaty, it’s urgent that we develop alternatives that curb national appropriation and ensure that space is used for the benefit of all humankind, not just the first and most assertive movers.

Reference: https://slate.com/technology/2023/09/space-law-commercial-mining-science-fiction.html

Ref: slate

MediaDownloader.net -> Free Online Video Downloader, Download Any Video From YouTube, VK, Vimeo, Twitter, Twitch, Tumblr, Tiktok, Telegram, TED, Streamable, Soundcloud, Snapchat, Share, Rumble, Reddit, PuhuTV, Pinterest, Periscope, Ok.ru, MxTakatak, Mixcloud, Mashable, LinkedIn, Likee, Kwai, Izlesene, Instagram, Imgur, IMDB, Ifunny, Gaana, Flickr, Febspot, Facebook, ESPN, Douyin, Dailymotion, Buzzfeed, BluTV, Blogger, Bitchute, Bilibili, Bandcamp, Akıllı, 9GAG