The Deep Sea Is Safe. Trust Me, I’ve Been There.

Reading Time: 5 minutesI Rode a Submersible to the Deep Sea. After the Titan Implosion, I Keep Thinking About What Happened Before We Launched., The vast majority of deep-sea exploration is nothing like the OceanGate disaster., What the Titan implosion could mean for the future

Let’s begin with the story of a beloved beard, sacrificed to science. In February 2020, I sat in a safety briefing for the DSV Alvin submersible with two proudly bewhiskered deep-sea scientists who had just been told they would have to shave. Each passenger on an Alvin dive must be fitted for an emergency breathing apparatus in case the cabin gets smoky or its two carbon dioxide scrubbers fail. These masks have only been used twice in 58 years. But still, they must fit, and to create a seal, there can be no hair in the way.

‘I look like Charlie Brown without facial hair, so I was not enthusiastic about it. But, safety first,’ said marine biologist and professor Craig McClain, recently recalling his moment of shock and dismay. The bearded scientists were permitted to keep handlebar mustaches.

I’m neither a millionaire nor a scientist; I was at the safety briefing for the Alvin dive because McClain, a friend of mine, had invited me to write about what it feels like, as a nonexpert, to visit the deep sea. He has studied the deep sea his whole adult life, but this trip would be only the second time he visited it in person. Together, we would travel 6,000 feet deep in the Gulf of Mexico in the Alvin submersible.

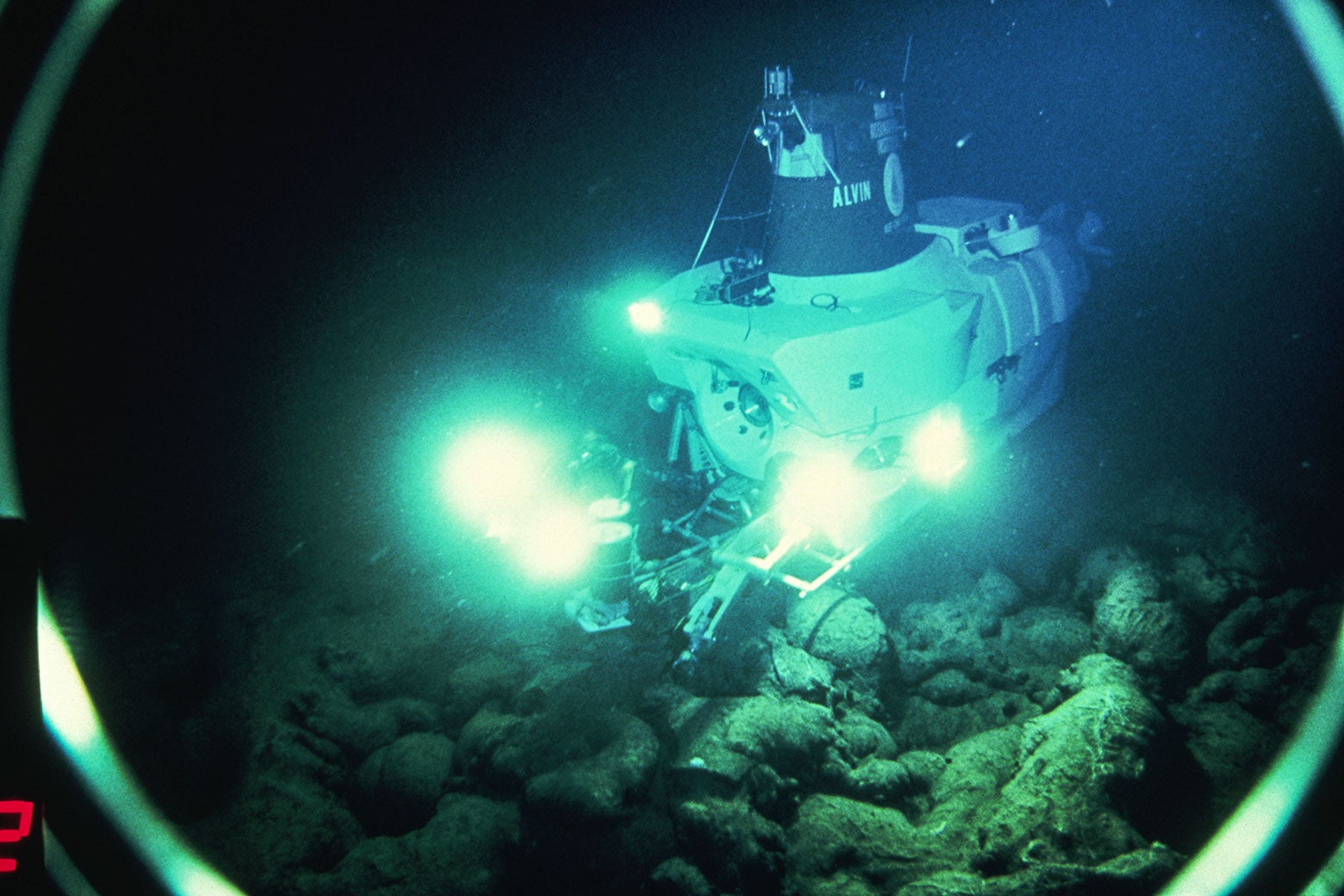

After the OceanGate Titan disaster, in which five people died when the submersible imploded, I think we can all agree that rich guys who cut corners do not make great submersible engineers. But scientists have been using submersibles for decades—and with the proper safety precautions, deep-sea dives are actually quite safe. The Alvin, for example, was one of the first research submersibles, and has completed more than 5,000 dives since the mid-1960s with no deaths or serious injuries—in fact, it is likely in the water right now. In addition to scientists, the Alvin has shuttled more than 10,000 observers, just like me, to witness the magic of the deep sea. Despite the pristine track records of the Alvin and other research submersibles like it, last month’s highly public submersible disaster is making some scientists concerned about the future of their work.

‘My scientist text thread is worried,’ McClain told me. ‘We don’t want this disaster to turn the public against deep-sea submersible research.’ This research, after all, is crucial to understanding our world—but if the public doesn’t understand how the research actually works, the Titan tragedy could deplete the pool of people interested in pursuing or supporting manned-submersible research in the future. Deep-sea research doesn’t exclusively use submersibles. Scientists quite often use remote-operated vehicles instead. But it’s hard to imagine having a career studying a habitat you are never allowed to visit—a robot with a camera is just not the same. For the public, research using submersibles like the Alvin sparks the imagination. ‘How many of those involved in the space program were motivated as children watching shuttle launches?’ McClain said.

Of course, it makes sense to be a little apprehensive about stepping into a 6-foot-in-diameter titanium sphere and dunking oneself a mile deep in the ocean. I was nervous before my dive. At the safety briefing, the first thing I asked the pilot was, ‘What happens if the battery dies or you have a heart attack?’

‘Nice to meet you, too,’ he said.

With those pleasantries out of the way, I learned the Alvin has six detachable steel weights attached to its hull. In an emergency, hermetically sealed switches inside the Alvin can release those weights, dropping them like sandbags. This lets the submersible ascend to safety. There’s also an operations manual inside—a literal three-ring binder with a laminated instruction card—that walks passengers through the safety information from the pre-dive briefing: how to release the weights, manage the oxygen in the sphere, and communicate with the surface in an emergency.

The next set of safety features took me by surprise. No cellphones allowed, no synthetic fabrics, and no citrus fruits. The phone makes sense. But synthetic fabrics?

According to the Alvin team, this is because synthetic fabrics are made with plastic, and ‘plastics have a lot of characteristics that we prefer to avoid.’ They can off-gas chemicals that aren’t great for enclosed spaces, and if there were a fire, well, plastic melts. As for oranges, when you peel one, the orange oils have a tendency to spray everywhere. In the presence of pure oxygen from the tanks on board, those orange oils have the potential to ignite.

I decided I could live without oranges for eight hours, but the synthetic fabric rule made me nervous, as I’m not in the habit of traveling with all-wool underwear. Which, in the name of safety, I had to tell the team.

‘Regular underwear is probably fine,’ they said.

Probably?

‘It’s fine,’ they said.

It is testament to these rigorous and smartly conservative safety protocols—and the fact that the Alvin is reviewed for safety by the U.S. Navy—that by the time I was in the sub with my regular underwear and zero oranges, my biggest worry was … a bathroom emergency. I was not excited about the specter of Alvin‘s 50-gallon garbage bag and roll of toilet paper, which would ensure me membership to what our pilot called ‘a very elite club.’ (Reader, I did not enter that club.)

Finally, as we descended through the water column, I marveled at the blue bioluminescent bacteria flashing all around as the water darkened like a night sky—from sparkly turquoise to daylight blue to twilight to midnight black. I saw a giant isopod—a football-sized underwater pill bug—in its natural habitat, and watched as it shook itself free from the seafloor and swam up over my head. I was calm and relaxed, oddly at home, listening to Queen’s ‘Bicycle Race’ on the cabin speakers.

Deep-sea research isn’t about visiting a tourist destination. We were there to retrieve ‘wood falls’—logs that McClain’s team had dropped to the sea floor many months previously. Using the Alvin‘s mechanical arms, we brought these logs to the surface and cataloged the slimy things that had been eating them. McClain’s research seeks to understand how food availability affects deep-sea biodiversity, building a clearer picture of these ecosystems and how they are affected by a warming climate.

The Alvin is regularly modernized and rebuilt, and thus has a long history of paradigm-shifting research and discovery: It was responsible for finding the Titanic in 1986 and a missing hydrogen bomb in 1966. It explored the devastation of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010. And in the 1970s, it confirmed the existence of giant worms that don’t photosynthesize like plants or breathe oxygen like animals or consume any plants or animals. They are ‘chemosynthetic,’ living on the sulfur gas emitted from hydrothermal vents. Before this discovery, no one knew life could survive without sunlight. The Alvin helped rewrite our understanding of the nature of life on earth.

As I sank in the Alvin, I felt emotionally connected to this strange world that was also my world. There are more mysteries in the deep sea than we can solve in our lifetimes, but the fact that we are able to try at all is because of the painstaking caution and care of people like the ones I dove with. When we came up early as a safety precaution for a low battery, I was sad to leave. I’m eagerly awaiting my next invitation.

Ref: slate

MediaDownloader.net -> Free Online Video Downloader, Download Any Video From YouTube, VK, Vimeo, Twitter, Twitch, Tumblr, Tiktok, Telegram, TED, Streamable, Soundcloud, Snapchat, Share, Rumble, Reddit, PuhuTV, Pinterest, Periscope, Ok.ru, MxTakatak, Mixcloud, Mashable, LinkedIn, Likee, Kwai, Izlesene, Instagram, Imgur, IMDB, Ifunny, Gaana, Flickr, Febspot, Facebook, ESPN, Douyin, Dailymotion, Buzzfeed, BluTV, Blogger, Bitchute, Bilibili, Bandcamp, Akıllı, 9GAG