The Complicated Legacy of a Brain-Injury Rock Star

Reading Time: 8 minutesTerry Wallis’ death and legacy for brain injury neuroscience.

A version of this article first appeared in Issues in Science and Technology.

I have been teaching a seminar on disability rights and brain injury at Yale Law School since 2015, and for years, despite the subject matter, I never came close to tears. But I choked up when I told my students about the death of Terry Wallis, at age 57, on March 29, 2022. Wallis came to international attention when he awakened from what was thought to be a permanent vegetative state after 19 years of being unresponsive, and his astonishing experience anchors what I hope will become legal frameworks that enable disability law to better meet the needs of patients with severe brain injury.

After an accident in 1984, Terry was considered by his care team to be in a state of permanent unconsciousness, until 2003—when he said ‘Mom’ and then ‘Pepsi,’ his favorite drink. In the years that followed, Terry became more interactive, recognizing and communicating with his family. In 2009, he told his mother, ‘Life is good.’

It’s not an exaggeration to say that Terry’s awakening set off a ‘golden age’ of brain science, profoundly changing the scientific, moral, ethical, and legal understandings of consciousness. Although Terry was exceptional—he became a brain injury rock star—his death was all too ordinary and, arguably, avoidable: a consequence of therapeutic nihilism about severe brain injury, widespread discrimination against people with disabilities, and inadequate rehabilitation facilities in the rural area where he lived.

The irony and injustice of the way he died affected me deeply. Despite the fact that neuroscience has learned so much from Terry’s remarkable journey, the United States’ depersonalized health care system neglected him, like so many others with severe brain injury. His death was a harsh reminder that the revolution in brain science that Terry helped launch will remain incomplete until scientific progress is matched by an obligation to bring these advances into clinical practice in ways that are meaningful and just.

In the near year since his passing, I have come to think that Terry’s death may be as important as his emergence for the way it encapsulates both the progress and peril of how society is coming to understand severe brain injury and frame its obligations to care for people who have experienced them.

I first met Terry and his parents, Angilee and Jerry, when they came to the Consortium for the Advanced Study of Brain Injury at Weill Cornell Medicine and Rockefeller University in 2004 to see if our team, which I codirect with neurologist Nicholas D. Schiff, could explain his emergence. I interviewed Angilee and Jerry as part of research for my book on the rights of those with severe brain injury, Rights Come to Mind, shortly after they arrived in New York from rural Arkansas. I gathered they felt out of place in Manhattan, but we immediately struck a connection when they realized that their concern for Terry was matched by our research group’s interest in his experience.

Nothing was more important to the family than Terry, whose medical course Angilee had tracked carefully since his car accident. She told me that the family thought they had seen glimmers of awareness over the years and had asked for a neurologist to reassess Terry’s condition, only to be told it was too expensive and wouldn’t matter.

Terry’s remarkable story had garnered international headlines and been hailed as a miracle, but my colleagues and I were not surprised by his recovery. Although he had been described as being in the vegetative state—that is, permanently unconscious—we suspected he had actually been in the minimally conscious state (MCS), a condition that was formalized only a year before Terry started to talk again.

MCS resembles the vegetative state but is distinct because MCS patients are conscious, albeit liminally so. They have awareness of self, others, and the environment. The challenge is that they don’t always manifest these behaviors and can appear vegetative when these signs are absent. But biologically, these patients are distinct from those in the vegetative state. The minimally conscious brain is functionally integrated and capable of communicating across widely distributed neural networks necessary to sustain consciousness. This contrasts with the functionally disintegrated vegetative state, which cannot work as a consolidated unit and thus cannot sustain consciousness. MCS patients exhibit behaviors reflective of awareness and consciousness: They may say a word, reach for a cup, or look up when you enter the room. However, these behaviors are usually episodic and intermittent, and such signs of ‘covert consciousness’ are easy to miss—and, if noticed, easy to dismiss as wishful thinking. One study found that up to 43 percent of nursing home patients diagnosed as vegetative following traumatic brain injury were in fact in MCS.

During the many years that Terry was lying in his nursing home bed, his brain had recovered.

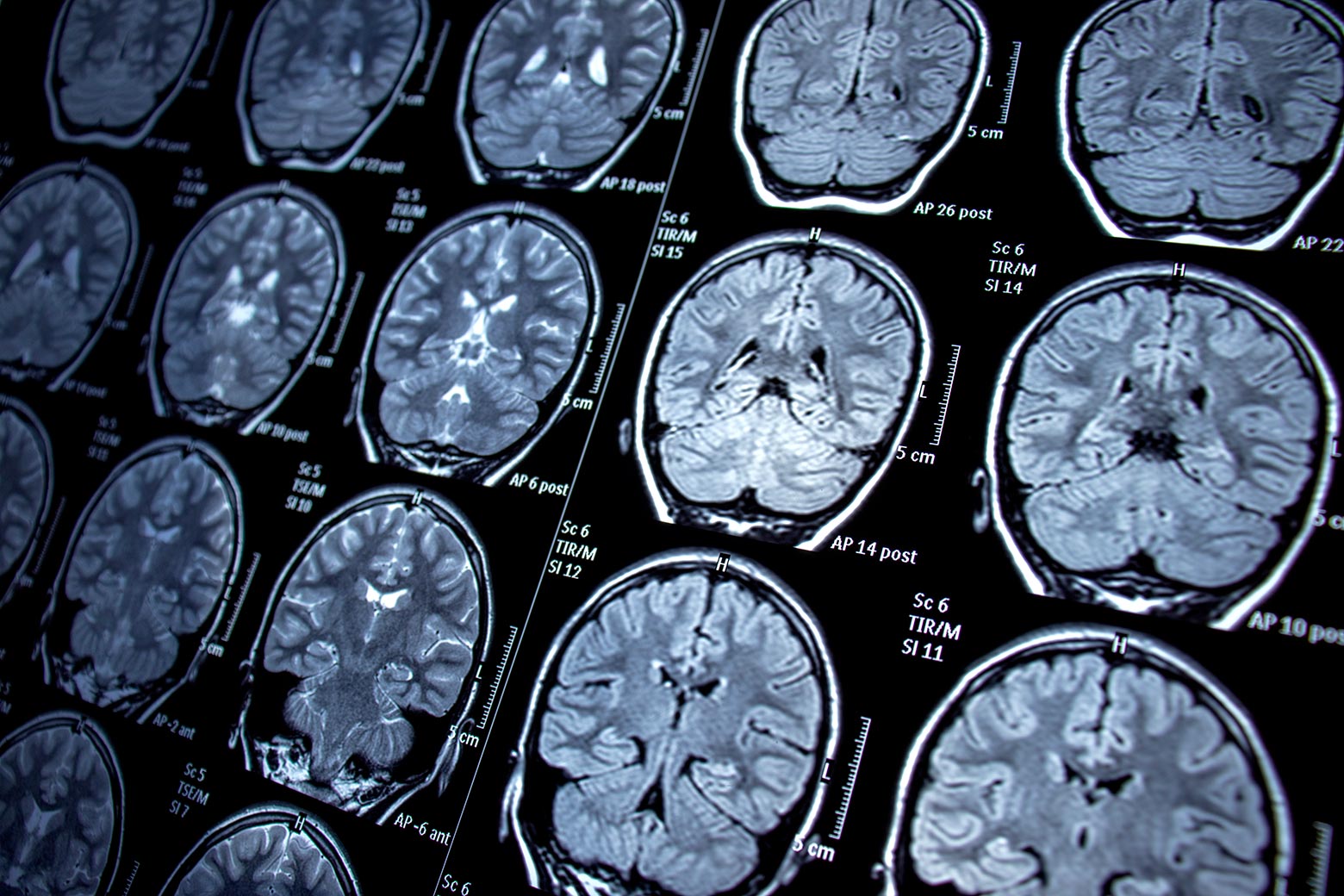

Imaging studies of Terry’s brain done by Schiff and our team found dynamic changes that might explain the improvement in his brain state.

Terry’s scans were stunning, revealing the potential of the injured brain to heal itself and carrying implications for how physicians view the depth and length of rehabilitation.

If brain recovery recapitulates brain development, which takes years, maybe the duration of rehabilitation should resemble that of childhood education, which is tailored to the developing brain. If rehabilitation is viewed as analogous to the educational process, then payments for its provision should be guided by the underlying recovery. Instead, they are often guided by the traditional reimbursement criteria of insurance companies, which presume stasis—often resulting in patients having to forgo rehabilitation efforts altogether. Brains recover by biological mechanisms, not reimbursement criteria.

In the two decades since Terry regained his voice, the science of disorders of consciousness—and the possibility of treatment—has radically shifted. Researchers have learned how to identify covert consciousness with functional neuroimaging, have begun to develop drugs and devices that can accelerate the return of consciousness, and now even consider the ethical implications of these advances. This progress culminated in 2018, when a new standard of care for patients with disorders of consciousness was issued by the American Academy of Neurology, the American College of Rehabilitation Medicine, and the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research. In addition to the use of emerging technology and drugs to assess and treat patients, the new standard importantly called for the amelioration and prevention of confounding conditions that effect the morbidity and mortality of these patients, such as bedsores, urinary tract infections, and pneumonia. If a patient succumbed to these conditions because of inadequate care, any progress in the diagnosis and treatment of their underlying brain injury would be for naught.

It was clear that Terry’s awakening had helped catalyze a promising era of neuroscience and prompted a moral consideration of what society’s responsibilities should be toward people with severe brain injury. Indeed, as the personification of MCS and example of what neuroscience was learning about severe brain injury, Terry’s passing was a major news event: The New York Times carried a full obituary with a photo, and I saw him featured as a ‘notable death’ on a national TV news show.

These cultural markers, however, only tell part of Terry’s story—celebrating his emergence. They don’t acknowledge how he died. That Terry was so well known makes the circumstances of his death all the more disquieting. With access to adequate care, I believe the complications that led to his death might have been prevented and treated. But for patients with brain injuries, who are often subject to what is euphemistically called ‘custodial care,’ such deaths are all too common. Access to high-quality rehabilitation is limited by geographic availability and insurance preauthorization requirements that tend to send such patients to nursing facilities rather than rehab. Thus there is a paradox: Scientific progress over the past two decades has not been matched by greater access to the latest standards of care. Without appropriate rehabilitation, patients cannot benefit from advances in neuroscience.

In January 2022, Terry developed pneumonia. Before participating in a decision to place him on a ventilator, his sister, Tammy Baze, called Schiff and me for advice. Tammy said that his doctors advised against the procedure because they couldn’t imagine that the life he led was worth living. But Terry had treatable pneumonia, and his family insisted he be treated like anyone else.

Later the family told us that doctors asked to remove the ventilator, saying that Terry seemed withdrawn—which they ascribed to the hopelessness of his brain injury. However, his family felt that his interactions with them hadn’t changed, but rather that he was still grieving his mother Angilee, who had died two years earlier. Furthermore, he couldn’t fully articulate his feelings with a tracheostomy in his airway. The family felt that because they couldn’t clearly understand his wishes, it would be wrong to withdraw life support.

Based on what the family told us, Schiff and I said that Terry needed access to pulmonary rehabilitation to regain lung function. A new doctor agreed, but there were no facilities nearby that had availability and were capable of providing the kind of rehabilitation he needed. There seemed to be a place out of state, but Terry was too frail for a long ambulance ride. He was transferred to a skilled nursing facility that could provide pulmonary support until he was strong enough to make the trip. Despite the best efforts of his family and care team, he died of pulmonary complications.

It would be a shame if the public only remembered Terry’s awakening and failed to acknowledge the policy implications of his death. Even though Tammy advocated for Terry and rallied support from his care team, without access to rehabilitation locally, his treatment was predicated on him becoming well enough to travel out of state. All of this speaks to the intersectionality—and compounding vulnerability—felt by people with severe disabilities. These challenges are amplified by poverty, limited access to health care in rural America, and historic crosscurrents about vulnerable people’s right to die and right to care. Safeguarding the rights of people with disabilities is especially critical when their lives are marginalized by so many complicating factors.

I didn’t get the chance to go to Terry’s funeral, which was near his home in Big Flat, Arkansas. He was buried next to his mother and—reflecting his sense of humor and his favorite soft drink—he wore a Pepsi shirt and his casket was decorated with red, white, and blue flowers. Tammy wishes Terry were still alive but is consoled, knowing that he could give Angilee a ‘hug for the first time in 38 years.’

When I started medical school, such vast questions around consciousness, treatment, rights, and responsibilities were not discussed or even considered. At the time, neuroscientists saw the vegetative state as one of futility, and so the dominant societal conversation was about the right to die.

Establishing this right for patients and families was vitally important, but the early association of the vegetative state with the establishment of the right to die has left an enduring presumption that severe brain injury is without hope. This can lead to implicit bias and premature discussions about end-of-life care, even as neuroscientists have developed increasing hope for treating disorders of consciousness. Terry Wallis’s experience reflects these tragic, embedded assumptions.

Nonetheless, evolving knowledge has opened new clinical and normative horizons for brain injuries. With a better sense of the prevalence of covert consciousness, the temporal frame for brain recovery, and an expanding set of therapeutic possibilities, the widespread neglect of brain-injured patients has become a societal challenge demanding a comprehensive, humane approach. Learning to identify covert consciousness and predicting its course are projects for the future of the field. But now that these possibilities have been proven to exist, it is no longer acceptable to look away and presume the worst.

As the neuroscience about disorders of consciousness has evolved, it has become clear that society has a pressing ethical and legal obligation to view consciousness as a civil right: if it is present, it must be recognized; if insecure, it must be supported. As researchers develop the technological means to identify covert consciousness and then to restore and sustain people with disorders of consciousness, society must begin to see this as a responsibility concordant with disability law and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

The ADA compels society to hear the voices of people with disabilities, respect their lives, and integrate them into the nexus of their families and communities. The law, and its aspirations, gives sobering context to the narrative of Terry’s life and death. And Terry’s death demonstrates that rights are necessary but not sufficient—they must be backed up by appropriate, accessible care, in every part of the country. Terry deserved better, and so do others who struggle under the burden of severe brain injury and are left isolated and away from the larger community.

Now that scientists are on the cusp of having the technological means to provide imaging, stimulation, and drugs that may allow for more human flourishing, the nation must begin to grapple more meaningfully with the care and regard of marginalized people with disorders of consciousness. Their plight is the civil right that we don’t often think about, but we must.

The author is grateful to Tammy Baze and the Wallis family for their permission to tell their story.

Ref: slate

MediaDownloader.net -> Free Online Video Downloader, Download Any Video From YouTube, VK, Vimeo, Twitter, Twitch, Tumblr, Tiktok, Telegram, TED, Streamable, Soundcloud, Snapchat, Share, Rumble, Reddit, PuhuTV, Pinterest, Periscope, Ok.ru, MxTakatak, Mixcloud, Mashable, LinkedIn, Likee, Kwai, Izlesene, Instagram, Imgur, IMDB, Ifunny, Gaana, Flickr, Febspot, Facebook, ESPN, Douyin, Dailymotion, Buzzfeed, BluTV, Blogger, Bitchute, Bilibili, Bandcamp, Akıllı, 9GAG