Lost in the Storm

Reading Time: 15 minutesMy 10-Year-Old Daughter Wants to Be Dead. When I Tried to Help, I Saw How Deep Our National Crisis Really Is., My 10-year-old daughter thinks she should be dead. When I tried to help her, I saw how deep our national crisis really is., How to help child wit

To tell the whole story would take a book, so let me start in the middle. Let me start in mid-March of 2022, a few weeks before my daughter, Ash, turned 10. Let me paint you a picture of a child brimming with life, larger than life, who only wants to die. Who writes this poem:

Who angrily swallows medicines that do not help. Who inherited her ecologist grandma’s eye for the tiny, beautiful things outdoors. Who adores her grandpa. Who has more style than I ever will. Who, since she was tiny, has had just two flavors of experience: ‘This is the BEST day ever!’ or ‘This is the WORST day ever!’—no in-between.

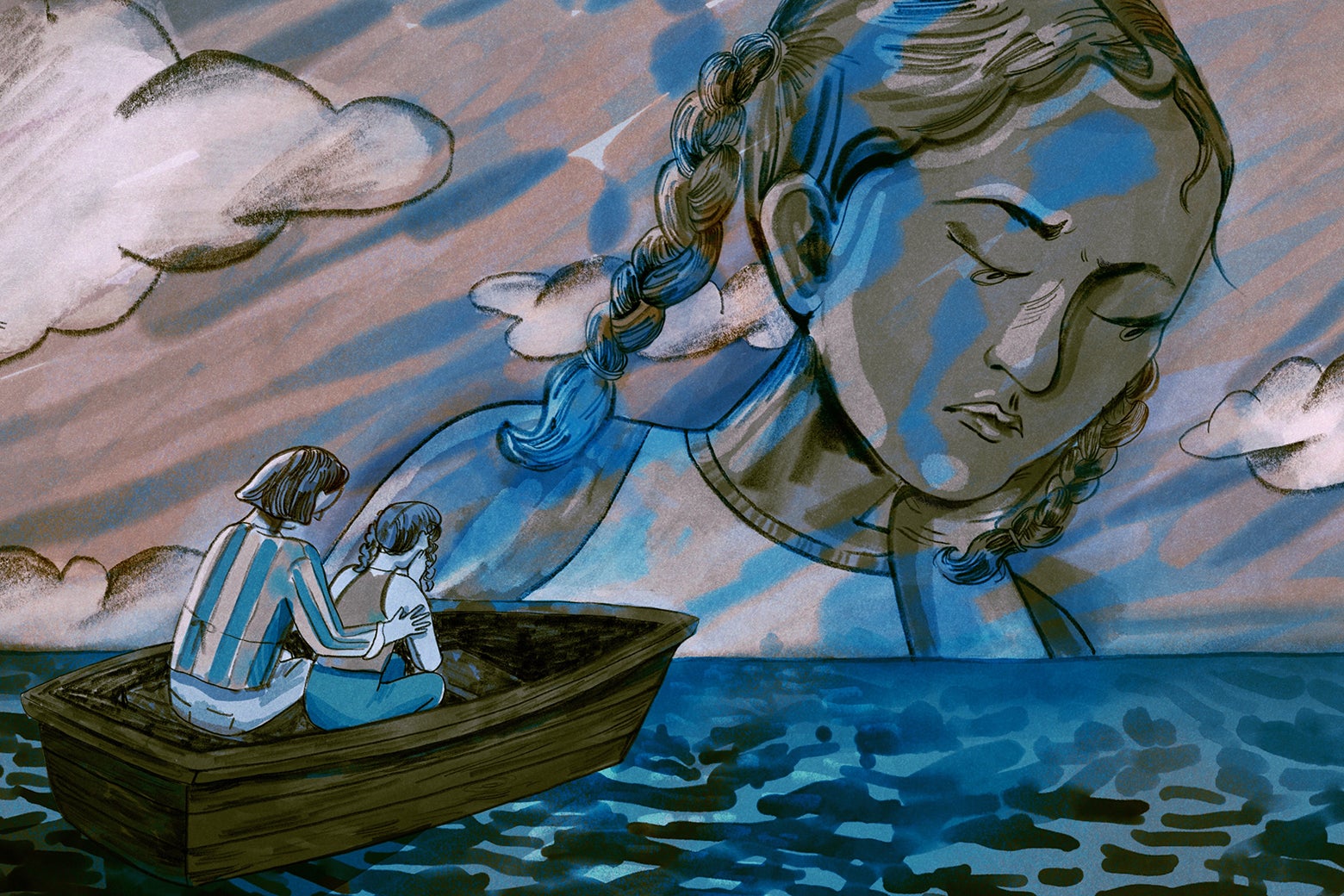

A chorus of voices, rising through the last decade (or more), has become a crescendo: We are experiencing a child mental health crisis. You could paper the Eiffel Tower with articles on this topic, very, very few of which have any real solutions. But as a mom caught in a small boat out in this perfect storm, I do not need these pieces to tell me what I have lived. I already know that trying to obtain humane therapeutic care for a child in crisis is no easier than trying to stop a hurricane. This is the story of my attempt.

In mid-March 2022, a few weeks before her 10th birthday, Ash was crashing hard. She cut herself with any sharp object she could find (of course we tried to keep everything we could from her). She wrote detailed, and remarkably consistent, suicide plans, which all culminated in everyone cheering her death. She refused to go to school. And she could not be calmed, no matter what we tried. Desperate, her dad and I followed her psychiatrist’s advice and scheduled an evaluation at a hospital in Virginia. I took her to the appointment, telling her that afterward we would go out for a treat.

But there was no afterward. Three hours later, we were told she was being admitted for inpatient treatment and could not leave. They took her shoelaces. They showed her to her room that was barely better than a prison cell. They pointed out the seclusion rooms, which were prison cells. They told me to drive an hour home, pack her a bag, drive an hour back, leave the bag with the receptionist in the lobby, then drive an hour home. And so I left her sobbing.

And so I left her, to call me over and over and over, screaming that she was in jail, screaming that she hated me, begging me to take her home. I left her in a place where the first contact we got from the social worker assigned to her was six days later at our discharge meeting, after Ash’s dad and I insisted they let her go. I left her in a hell where the stuffed dog she never let go of—which I thought she would be able to keep with her at all times as a comfort object—could not be carried out of her room, because maybe she might find something dangerous somewhere else in the ward and rip out the dog’s seams and stuff the dangerous object in and then later use it to cause harm to herself. I left her in a place that allowed only 90 minutes of visiting time every other day, which I spent sitting in her cell, holding her as she wept and begged me to take her with me. I left her.

By the time we insisted she be discharged, the only thing they had done was switch her medication. That’s it, in six days. After we took her out, they wanted her to attend their partial hospitalization program, and we reluctantly agreed, seeing no other option. But after half a day of that, after she got in my car in tears and told me that they had banned her comfort object, I knew we would never go back.

We managed somehow to get her through to the fall of 2022, but as school started back up in August, she started to spiral again. And that is when everything fell back apart.

Ash attends a public school in a large and well-resourced Maryland district. She is considered ‘twice exceptional,’ in that she has a severe emotional disability but is also advanced academically. She is also an internalizer, which means she never gets in trouble at school, just quietly falls apart without disrupting others.

Her school district is exceptionally good at public-facing verbiage about supporting student mental health, and, it turns out, incredibly difficult to maneuver in when it comes to actually accommodating a fragile child who doesn’t cause any disruptions except to her own learning.

And so we spend much of our time (and resources) trying to secure an appropriate therapeutic school placement for Ash, largely to no avail.

Let me pause here to say: Ash’s dad is a neurologist, and I am an educator and attorney with an expertise in special education. Ash has access to therapists, a psychiatrist, an excellent pediatric practice, and two parents who, despite being divorced, can work very well together to help find the best options for her. There are few limitations on what we can do, except we do not have the wealth necessary to send her to a boutique private school or private program. So we have to navigate the options available through the public schools and through insurance, supplemented with what we can afford to pay for therapy. We have a special-education advocate who specializes in school-avoidant, internalizing kids like Ash, and, later in the school year, we hired excellent attorneys. And so we begin the year feeling confident that we are in a strong position to get Ash the help she needs at school.

By October, though, Ash is spiraling again—leaving class up to two dozen times a day to visit the counselor or the nurse or to just sit in the bathroom and cry. Within the first weeks of the academic year, the school tells us that they are not equipped to help her. When we convene with her team in early November, the district insists on placing her in a different school, but the program there is designed for kids who have very different emotional disabilities than she does, and she would not have access to any accelerated classes (which is illegal).

Nonetheless, in a show of good faith, I visit the program, where I observe a concrete-block cell at the back of the classroom she would be in, containing only a single mattress on the floor. Apparently, after seclusion became illegal in Maryland, they took the door off and made it a ‘calm-down room.’ I try to imagine Ash, day after day, being forced to relive her hospital trauma in this classroom. The staff member giving me the tour proudly describes their main strategy for managing their students: sticker charts that can earn them ‘Fun Fridays.’ I am sure there is no double-blind study proving that Fun Fridays are an effective treatment for suicidal depression, so I head home certain that this is the wrong school for Ash.

We decline that placement. This results in a back-and-forth with the district that goes on for months, due to a number of factors, one of them being the district’s pretextual and endless—and I do mean endless—’rescheduling’ of meetings at which we might come to a solution. Every time we think we are making progress, a new roadblock is put in our path, and by the time we file state and federal complaints—which ultimately are the key to getting anything done—it is April.

In the meantime, Ash’s mental health deteriorates precipitously. Through the fall, she refuses to go to school, or when she does go, they invariably call us to tell us she needs emergency mental health care, and they send home a suicide risk form and a crisis center referral form and either ask us to pick her up immediately or assign a staff member to stay with her all the time.

At her dad’s house, she is agitated and angry. At my house, she is depressed and anxious. And she starts having frequent panic attacks, which for her manifest as complete paralysis—she cannot move or see or hear anything—and which leave her shivering, her palms and forehead clammy, with deep grooves in her hands from where she’s grabbed on to the nearest piece of furniture to steady herself as the darkness descends. She writes, of these episodes:

And so we start her in art therapy. We start her in dialectical behavioral therapy (or DBT)—both in a group and with an individual therapist. We research every option for residential treatment or partial hospitalization or outpatient treatment, and she is either too young or the waitlist is months long or the program is too far away. We ask all of the professionals, but they are hammers in search of nails. The psychiatrist recommends changing medications again, even though lithium and two different antipsychotics have not helped at all. The DBT therapist recommends more DBT, maybe at a residential program in Indiana or one in Virginia where a kid died in their care during a restraint less than five years ago. And the school does not know what to recommend—they just know they cannot provide her with services there.

Things come to a head the day before Thanksgiving. We have been taking Ash to extra sessions with her new DBT therapist, and her dad takes her to a session Wednesday morning, after which we get a call from the therapist and the head of the practice. The practice head, who has never once met Ash and has not had a single helpful thing to say to us since Ash started group DBT therapy in September, tells us that based on the therapist’s assessment, Ash is not safe at home and we must take her to the emergency room immediately, or else they will sign an emergency petition to have her removed by the police from our care.

Our jaws drop. These people—who we pay to help Ash—are forcing us to do the one thing that we know will hurt her far more than it helps: take her to an overcrowded and underfunded ER, where if she is admitted, she could easily get trapped in a hospital unequipped to help her. If she is transferred, it may very well be to a unit that takes the same liability-based, anti-therapeutic approach as her last hospital experience. Ash still has nightmares about that hospital, and sometimes I find her in her room, holding an artifact from her stay there, weeping, consumed by terrible memories. I have promised her over and over that I will not ever again make a quick decision based on fear—that whatever we choose going forward will be based on research and conversation and what we agree is best for her. Forcing me to break this vow, forcing Ash into the very environment that compounded her mental health crisis, will harm her deeply.

We try to explain this. They refuse to listen and insist their judgment trumps ours. I hang up the phone, frantic, and start exploring options. By some stroke of luck or grace, I text a friend who has been through a similar experience with her own child, and she tells me to take Ash to the Montgomery County Crisis Center. We can get a second opinion there, and maybe avoid the ER.

That evening, I wait with Ash on hard plastic chairs in a tired room where the only other person is a woman sitting with her legs propped up on her suitcase laughing hysterically at something we cannot know. We are quickly called into an evaluation room where a social worker who toggles between empathy and no-nonsense officiousness spends the next 90 minutes interviewing Ash and me, then Ash alone, then both of us together again. Ash is shutting down, as she often does when she feels like she’s being interrogated about her mental health, and I can see the social worker is getting frustrated. Finally the social worker stands up and says, ‘I’m sorry, but that’s it. If she cannot talk to me and demonstrate she can be safe at home, I am going to send you to the ER, and my decision is binding.’

I turn to Ash, panicking. I want what is best for her, but I feel to my very core that what is best for her is to spend Thanksgiving at home while we continue to search for whatever options might actually help her. But what if I am wrong? Ash has been swinging back and forth between begging to be allowed to come home and fiercely insisting that we have to take her to the hospital, but she is 10; she is so little, and being forced away from her family is a soul-gutting prospect.

‘Please,’ I say to her. ‘Help us understand whether you can be safe at home for Thanksgiving. We’ll figure out what to do next, and we will keep working to get you help, but if you cannot promise safety, we have to go to the ER. Can you be safe with me over the holiday?’

She says she wants to be home, she wants to see her grandpa and my boyfriend, who is coming over for Thanksgiving and who understands her in a unique and beautiful way. After some more back-and-forth with the social worker, I am free to take her home. I exhale, possibly for the first time all day, and we head out into the night.

On Thanksgiving morning, Ash’s dad calls around to inpatient units that have a better reputation than the hospital where Ash went in March. Even though he is a doctor, and speaks the language they know, every call is fruitless: No one will share information on capacity with anyone other than a referring physician in a hospital. The only option is to go with Ash to an emergency room and hope that they can transfer her to a good inpatient unit, and hope that the wait isn’t days, and hope that the first bed that opens up isn’t like the place she went last spring.

Luckily, her dad discovers that a local hospital with a stellar reputation has an emergency center that can evaluate Ash and potentially get her admitted to a strong program. We ask Ash if she can stay safe through the weekend, and we make a plan to take her to the hospital on Monday morning. We know that we are taking a terrible risk, but what else can we do? There are no choices. There is no help.

As if to drive this point home with a mallet, on Sunday we receive an email from the DBT practice. In the email, they lay out a plan that is required if Ash is to continue in their care. According to them, Ash must continue with six courses of DBT group therapy, which costs $1,200 for each of the six-week courses. She must attend extra therapy with her individual therapist, at $170 for each 45-minute session. We must also have phone calls and sessions with other members of the practice, billed at $115 for 30 minutes, $170 for 45 minutes, and $225 for one hour, in order to create and maintain a safety plan for Ash. Her dad and I must sign up for weekly DBT parent therapy, at the same rates. And we must consult with one of two ‘placement consultants,’ who no doubt charge hundreds if not thousands of dollars for their services, to find out if there are decent options for Ash for a higher level of care.

I do the math. Nine months with this practice will cost us over $25,000, conservatively speaking, and that’s without even factoring in the placement consultant, whose cost is unknown. And under all of this is the echo of the threat they have just made: That they will not hesitate to call the police and have Ash taken from us if at any point they decide—independent from our judgment or perspective as parents—that Ash should go to the emergency room. I stare at the email, not knowing whether to cry or laugh. Something in me is breaking, though, and breaking hard.

A small window finally opens on Monday, when Ash’s dad takes her to an intake session at a very highly regarded children’s psychiatric hospital in Baltimore. This time, we are far better prepared. We know that the program is a good one. We have Ash’s full agreement to the intake and possible hospitalization, and she is in a good mood as she packs her bag.

She is cooperative through the intake, and when they make the decision to admit her, she is ready.

That night, on the phone, she cries a bit because she misses us, but she soon settles in, and spends the next 10 days there, working with an exceptional team, a psychiatric nurse practitioner and a social worker who communicate with us frequently. We visit once on the weekend, and she is cheerful and happy to return to the unit when the hour is up. For the first time in months, I feel my heart unclench a bit.

But of course, the feeling does not last. When she is discharged, it is with the recommendation that she attend a step-down program—some sort of intensive outpatient therapy program that can give her a couple of months of support. We do the research and find two: One is only virtual still, which we know from experience is not helpful for her, but the other one looks good. Luckily, there is no waitlist, and since I have been approved for family medical leave, I can take her three days a week, from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m., even though the program is an hour away.

Two days before the program starts, we get the schedule. We think there must be a mistake—the program is set for 4:30 p.m. to 7:30 p.m., three weeknights a week for eight weeks. We reach out to the group, and they confirm that their hours have changed. With two other kids at home, spending five hours out of the house three evenings a week is a nonstarter. We’re out of luck again.

Now we turn to looking for a therapy practice that can see Ash regularly, in the hopes that someone really good can build a long-term relationship with her. All of the best therapeutic options are at least 30 minutes away (in wealthier neighborhoods than ours), but we are prepared to take any option, even if it means contorting our work schedules (to the extent possible) to take her. Luckily, we have access to a care manager through Ash’s dad’s insurance, which covers Ash. The care manager is instrumental in identifying therapy practices that might be a good fit—someone who might understand Ash, who will not be frightened away by her illness, and who has availability. Because we have gotten used to paying out of pocket for therapy, the prospect of covered care feels miraculous.

After calling around and joining waitlists and doing a few intake sessions, we find a therapist at a reputable practice not too far from our house who has an opening for Ash. Even better, the practice has psychiatrists on staff, and we are hopeful that she can transition to having all of her therapeutic and psychiatric care managed by one team.

Five sessions later, the ceiling falls again. The therapist will not commit to working with Ash. She sends Ash out of the room and tells us that Ash needs more intensive help than she can offer. She is discharging Ash from her care, but offering four last sessions so that ‘Ash can learn to say goodbye.’ I am crying as I tell her that Ash has said goodbye more times than any 10-year-old should have to.

The therapist says that her recommendation is the same as the hospital’s discharge recommendation—an intensive outpatient program. But in my view, these programs do not exist. The only two programs that are even remote possibilities are not real options because one is virtual and one is not accessible for our family. She mentions a residential program in Indiana that the hospital team has recommended against because it is a residential program, and thus above Ash’s set of needs. We find ourselves in a landscape that would have Kafka reaching for his pen: Ash is too sick for any therapist to work with her on an outpatient basis, but she is not sick enough to qualify for a therapeutic placement through her school district, either. I am almost (almost) laughing through my tears.

In late February, a space opens up in the virtual program that we had decided against in December. Because we are desperate, we start Ash in the program. The program lasts for six weeks, and it is three evenings a week, for three hours at a time, all on Zoom. Nine hours of virtual group therapy every week would test the patience of anyone, and Ash is no exception. She absolutely hates it. I am proud of her for persisting, since we really have no other option. At our final meetings with the therapist and psychiatrist, Ash is adamant that the program has not helped her at all.

In the meantime, the family medical leave I had applied for in December in order to stay with her has ended. With my boss offering no flexibility, I have no choice but to quit my job, giving up my financial stability to care for her. I start looking for jobs, cutting my spending, and spending my savings. It is scary and stressful. At the same time, the office in our school district responsible for the home tutoring Ash qualifies for ghosts us for two full months, leaving me solely responsible for keeping her caught up with her learning.

So here we are, six months after Ash’s hospitalization, with no school placement, no educational services from the district, and no regular therapy other than her lovely art therapist, who is wonderful and refuses to quit on Ash, but cannot address her more serious needs.

In some ways, Ash has gotten better over these months, which I attribute mostly to her being home every day with me. The cutting has subsided. She has not written a suicide plan in many weeks. But she still reports feeling sad most of the time, she still is highly anxious, she still has daily panic attacks, and she is not otherwise any better than before. Also, she has been deprived, for the most part, of the oxygen of friendship with children her own age, and that is hard to watch. By the end of the school year, Ash has not been able to attend any school since November. She cries almost daily about being cut off from other children her age, about missing her elementary school promotion ceremonies, and about how the exclusion makes her feel broken and unlovable. ‘I miss sitting in class, Mom,’ she says. ‘I miss just learning with my friends.’ I get that, and I feel for her.

Ironically, despite the mind-bending madness of these weeks and months, I recognize that we are relatively lucky. Our child is a danger only to herself, not to others. Many desperate parents have fallen victim to vile and unscrupulous programs that are designed to take advantage of families at their most vulnerable—when their children are too out of control for school or home. Even as I write this, a friend of mine sits in a hospital with her son, day after day, waiting for a psych bed to become available. Other friends are going about their days desperately missing children who are living in residential treatment centers far away. But of course we don’t feel lucky, because we are just trying to keep our daughter alive. That is everything to us, even if it is a private kind of hell that does not threaten others.

Swirling through all of this, I think about what Ash and thousands of other children like her are trying to tell us: That the world that we have created for them does not work for them. That the world we have created, plus a global pandemic and so many other unaddressed crises in public life, does not work for them … or anyone. But because they are children, and because it is clear that we are not wise elders, but just flawed people stumbling in the dark, the way that this all plays out is that they are destroyed from the inside, and that explodes outward in a myriad of terrifying ways—suicide, self-harm, school avoidance, failure to launch, school shootings, and on and on and on. There are precious few who are able or willing to help, and even fewer who are willing to work for the possibility of a future where kind, empathetic therapeutic care is available to any child who needs it, where our public schools work for all kids, and where the adults in charge are thoughtful and humble and wise enough to listen to what our young people are telling us.

We do not hear them clearly, and we keep not hearing them clearly. Instead, we stick to our old systems, which never worked and still don’t work. And for those of us in our small boats in the storm, there is no sunlight, no clear horizon. There is only a small slip of moon to ebb the surging tide.

Reference: https://slate.com/technology/2023/06/child-teen-mental-health-crisis-therapy-help.html

Ref: slate

MediaDownloader.net -> Free Online Video Downloader, Download Any Video From YouTube, VK, Vimeo, Twitter, Twitch, Tumblr, Tiktok, Telegram, TED, Streamable, Soundcloud, Snapchat, Share, Rumble, Reddit, PuhuTV, Pinterest, Periscope, Ok.ru, MxTakatak, Mixcloud, Mashable, LinkedIn, Likee, Kwai, Izlesene, Instagram, Imgur, IMDB, Ifunny, Gaana, Flickr, Febspot, Facebook, ESPN, Douyin, Dailymotion, Buzzfeed, BluTV, Blogger, Bitchute, Bilibili, Bandcamp, Akıllı, 9GAG