Inside the Human Urge to Tinker With Other Species

Reading Time: 5 minutesDe-extinction and conservation: When introducing a new species goes wrong.

A conservation researcher responds to Torie Bosch’s ‘Bigfeet.’

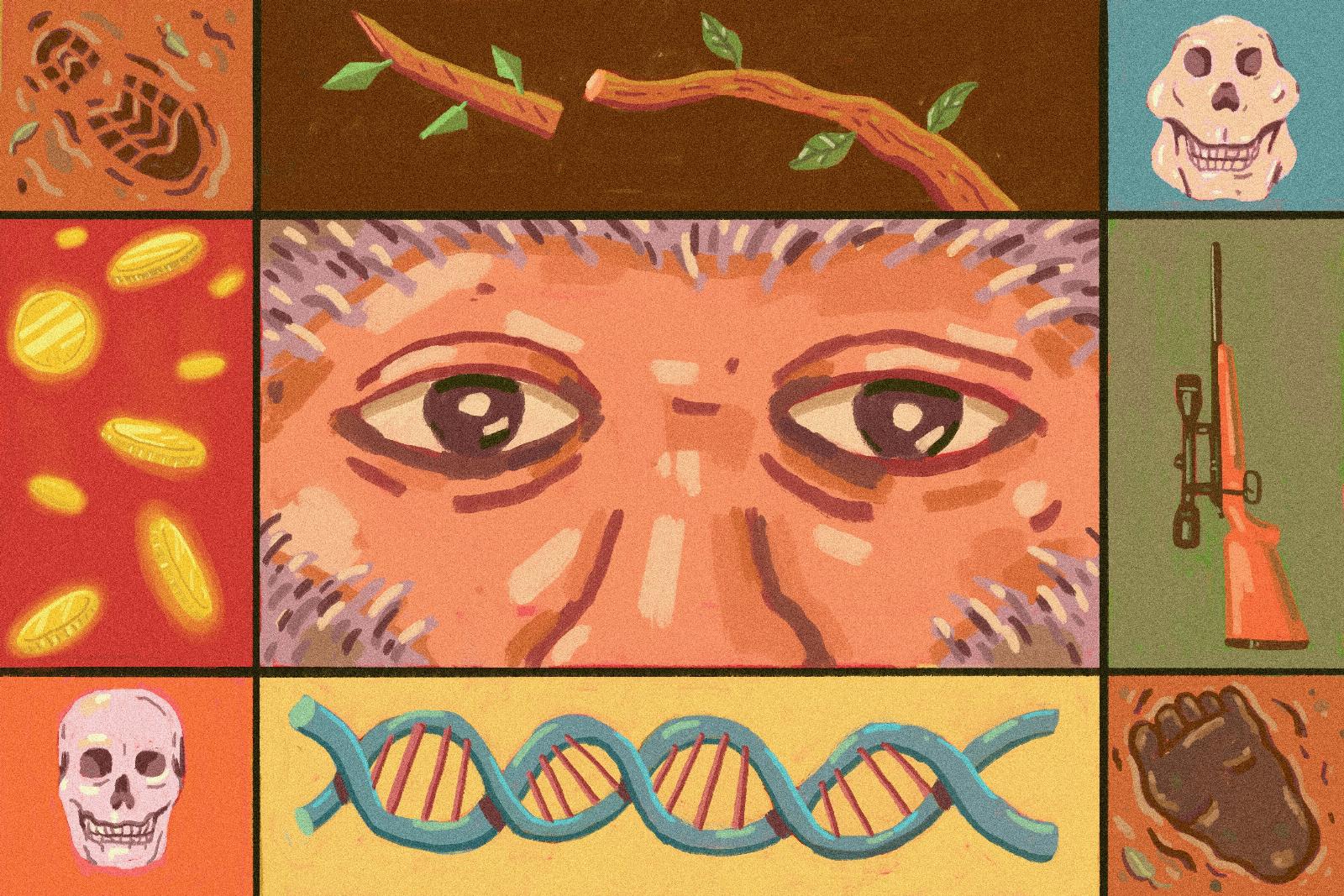

I was once chatting with an environmental historian who made a comment that stuck with me: Humans are of the species Homo tinkerus. Their point was that restraint is difficult for people, particularly in our environment—we love to change things. Historically, these interventions centered on human pursuits, like explorers trying to recreate English gardens or hunters introducing preferred game into an area. But as the disastrous effects of human activity on the Earth’s ecosystems have become undeniable, some humans have turned their tinkering impulse to modifying the environment to reverse damage our species has done. And while there’s merit in trying to correct our own mistakes, history has taught us that even pure intentions can’t protect against unexpected—and potentially dangerous—consequences.

Torie Bosch’s story ‘Bigfeet,’ styled as a magazine feature for the fictional, New Yorker-esque publication Matter of Fact, presents a dramatic example of humans tinkering in ecosystems, and the potential strange and unforeseen environmental (as well as legal and social) fallout. Dr. Shelley, the anonymous scientist at the heart of the story, describes how Bigfeet—genetically engineered approximations of the legendary cryptid—were created and then dropped into forests throughout North America, with little thought about what might happen to them or to other species they’d cohabitate with.

This fictional scenario has many real-world counterparts: In the 1920s, sport hunters released a dozen mountain goats on the Olympic Peninsula in western Washington state—the same region where some of the story’s Bigfeet are set loose. Like the Bigfeet, the mountain goat population grew out of control quickly. The goats have caused problems since, from eating sparse alpine plants to trying to lick salt off hikers’ clothes and gear—salt deposits don’t occur naturally in the peninsula, but the goats need it in their diet. As a result, federal and state land managers were forced to carefully devise a multiyear plan to relocate or extirpate the goats (including lifting some by helicopter to more suitable habitats).

The list of other examples is long: rabbits in Australia (also for sport hunting), invasive ornamental grasses in Arizona, and even rats unwittingly stowing away to far-flung islands on ships. Each has resulted in ecosystem problems that then need to be corrected with further interventions, potentially causing a cascade of additional consequences. The scientists working on the fictional Bigfeet project hoped to create a large herbivore that could serve as a food source for predators and add nutrients to soil through its droppings, but over time, they also realized that their grand endeavor was, at its core, a billionaire’s revenge project. While the Bigfeet are a huge hit with tourists and a global media phenomenon, they’re already causing agricultural problems and threatening the food source and habitat of an endangered species.

In the Pacific Northwest, the Bigfeet start feeding on harsh paintbrush, one of the host plants for the endangered Taylor’s checkerspot butterfly, decimating the butterfly population. In response, the U.S. government fines Thomas Bunch, the magnate behind the Bigfeet project, who also faces jail time (though he has disappeared). But a nominal fine and a few months behind bars do little to compensate for the loss of a species. Butterflies are important pollinators and could be the canary in the coal mine for species in ecosystems invaded by Bigfeet, whose dietary needs and preferences are still ill-understood and could result in cascading destruction.

There are larger potential effects from the introduction of the Bigfeet, rippling out from local ecosystems. Through the climate crisis, humans are in the process of altering every inch of the Earth, from ocean floors to mountain summits. Bigfeet are a chimera, created by combining the DNA of multiple animals, from the extinct primate Gigantopithecus to bonobos and black bears. One of the animals included is cow, which adds a moment of levity to the story when we learn about the Bigfeet’s mooing call. Livestock—and in particular their burps—are a significant contributor to climate change. Cow burps contain methane, a greenhouse gas that traps 28 to 34 times more heat in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide. Cows and other livestock are responsible for 40 percent of global methane emissions. The Bigfeet’s bovine heritage is doubly concerning for the climate because they reproduce quickly (which some observers in the story ‘cheekily’ speculate could be thanks to rabbit DNA), thus compounding their environmental effects.

The ethics around all of this—in real life and fiction—are mind-boggling. Mitigating human impacts on landscapes forces scientists and land managers into difficult decisions. Judging the long-term effects of specific interventions takes a lot of research, and even then, it can’t account for everything. Take for example the greater glider, a small, long-tailed marsupial that went locally extinct within Australia’s Booderee National Park around 2010. One theory for its disappearance is that when land managers reduced the population of red foxes, forest owls may have adjusted their diet, eating more gliders and eventually wiping them out.

Introducing a novel species isn’t a decision that land managers would take lightly—hence the secrecy and extralegal nature of Bunch’s project. Though Bigfeet are a ‘designer species,’ crafted to align with Sasquatch lore, de-extincting an actual historical species is a very real proposal, and one that’s sometimes meant to hypothetically protect and enrich the environment. Woolly mammoths, extinct for thousands of years, have been proposed as a target for de-extinction, and scientist George Church is actively trying to bring them back to Siberia. He theorizes that mammoths, by stomping around, could change the moss-dominated Siberian landscape into a grassland, which better locks in carbon and could help combat climate change.

Other proposals, like those to de-extinct the passenger pigeon, aim to correct a previous human error. Passenger pigeons were once so numerous in North America that European settlers described skies turned black as night by their mass migrations. But overhunting and habitat loss (thanks to settlers clearing forests for farming and logging) decimated their populations. The last passenger pigeon died in 1914; proposals to bring this species back rely upon modifying the genes of band-tailed pigeons to mimic passenger pigeon traits. Some scientists hope that de-extincting the passenger pigeon will help restore forest regeneration cycles, leading to healthier and more biodiverse landscapes. In an ecosystem that has not seen this species in more than a century, such a happy ending is far from guaranteed.

The revenge project described in Bosch’s story provides a great example of the risks of meddling in ecosystems; it also broaches the ethics of tinkering with species composition and genetic modification. Gene editing tech like CRISPR-Cas9 can be an amazing tool with seemingly limitless uses. When looking at ecosystems, though, tremendous thought and care ought to go into decisions to use it. There have been many well-intentioned proposals for species modifications (though none as drastic as creating a Bigfeet chimera), such as modifying bees to resist parasites and viruses that can lead to colony collapse, or modifying mosquito populations to cause them to die out, protecting humans from diseases like malaria. Though tinkering with species and ecosystems is tempting for a variety of reasons, from safeguarding vulnerable humans and animals to undoing grievous damage caused by human activity, our inclination to meddle often leads to even more tangled chains of cause and effect.

Reference: https://slate.com/technology/2023/01/deextinction-species-introduction-conservation.html

Ref: slate

MediaDownloader.net -> Free Online Video Downloader, Download Any Video From YouTube, VK, Vimeo, Twitter, Twitch, Tumblr, Tiktok, Telegram, TED, Streamable, Soundcloud, Snapchat, Share, Rumble, Reddit, PuhuTV, Pinterest, Periscope, Ok.ru, MxTakatak, Mixcloud, Mashable, LinkedIn, Likee, Kwai, Izlesene, Instagram, Imgur, IMDB, Ifunny, Gaana, Flickr, Febspot, Facebook, ESPN, Douyin, Dailymotion, Buzzfeed, BluTV, Blogger, Bitchute, Bilibili, Bandcamp, Akıllı, 9GAG