Æon Flux’s Surveillance Aesthetic

Reading Time: 7 minutesThe 1990s MTV Cartoon With a Surprisingly Modern Take on Surveillance, The 1990s MTV animated series has a bracingly contemporary take on privacy., Æon Flux’s surprisingly modern take on privacy and surveillance.

Perhaps no piece of science fiction relies less on text and linear narrative, and more on visual style and tone, than Peter Chung’s Æon Flux—not Karyn Kusama’s visually stunning but unfulfillingly straightforward live-action film from 2005, but the 1990s animated series created for MTV’s Liquid Television. The series resonates powerfully with our contemporary obsession with, and confusion over, a web of ideas about surveillance, privacy, transparency, spectacle, performative acts, and the ethics and effects of watching and being watched. Decades later, Æon Flux still presents a fresh alternative to black-and-white moralizing about life in a surveillance society. It takes the oppressive power of surveillance seriously, but it’s stubbornly playful, unafraid to point out how often we willingly expose ourselves to the all-seeing lens.

Chung, a veteran animator known for his work on Rugrats, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and The Transformers, builds an aesthetic that blends Japanese anime, German Expressionism, and cyberpunk. His angular, spare, often brutalist urban landscapes are populated by elongated, distorted, fluid human characters drawn in the style of 19th-century Austrian portrait painter Egon Schiele.

The series unfolds in Monica and Bregna, two neighboring futuristic cities that find themselves perennially warring, though the cause and stakes of the conflict always remain murky. Bregna is the locus of much of the series’ action, with the titular Æon, a trickster secret agent, navigating the byways and interstices of the city, a surveillance state run by the irresistible rascal Trevor Goodchild. Æon and her counterparts are clad in high-tech fashions that marry the patent leather and harnesses of BDSM scenes with techno-fetishistic spy thriller touches (think James Bond’s ziplines, spyglasses, and fancifully enhanced handguns), plus stormtrooper-esque helmets and body armor drawn from steampunk and dystopian science fiction, calling to mind the fascist military raiment of World War II.

In memorable works of science fiction, the tone, style, and technological accoutrements that make up a particular vision of the future endure as much as, or more, than the plot and character arcs, from the dusty, weather-beaten grandeur of Star Wars‘ Tatooine to the black trench coats, narrow sunglasses, and bullet-time ballet of The Matrix. It’s equally true in literature: Think of Isaac Asimov’s ruminative, often formal prose style in his classic Robot stories (‘The radical generalization offered it, i.e., its existence, not as a particular object, but as a member of a general group, was too much for it’) or Ursula K. Le Guin’s self-aware narrator in The Left Hand of Darkness acknowledging the partiality of his own account, emphasizing the author’s anthropological approach to life and culture on the planet Gethen (‘The story is not all mine, nor told by me alone. Indeed I am not sure whose story it is; you can judge better’).

Æon Flux‘s narratives are famously cryptic, its morality opaque, and Chung’s priority is aesthetic; he told Sound magazine in 1992, ‘I was interested in experimenting with visual narrative, telling a story without dialogue […] For me there is a solid storyline going on under all the action. It’s not really that important to me whether or not everybody agrees on what that story is.’ Later in that same interview, he says, ‘What’s interesting to me about filmmaking is that it’s not a literal, linear medium. … [I]t’s all external imagery, it’s all physical.’ And the most externalized, tangible aspect of Æon Flux‘s style is its fascination with surveillance, transparency, and what happens to people when they are secretly watching, or suspect they’re being watched, or feel confident that nobody is looking.

Which might lead you to believe that Æon Flux is eerily prescient, or freighted with invaluable lessons for grappling with the messy landscape of technology and society today. Alas, the series doesn’t have any answers for us—it doesn’t make policy prescriptions or stake out any philosophical terrain. What it does superbly is to dramatize the difficulty of disentangling surveillance from curiosity, eroticism and desire, our hopes to hold power to account, and the pleasures we take in putting on a show. Its science fictional world helps us to appreciate why it remains so difficult to define our terms when we try to talk about ubiquitous surveillance and its consequences.

Æon Flux started as a series of dialogue-free vignettes of two to five minutes, aired by MTV in 1991 and 1992, with the main character dying (!) at the end of each episode. In 1995, the network aired a 10-episode season of half-hour episodes, with dialogue, flirting with if not settling on more continuity. The first longer episode, ‘Utopia or Deuteranopia?’ is particularly concerned with surveillance, transparency, and voyeurism—and, happily, is currently available for free online streaming at MTV’s website.

The episode has a fairly clear plot, by Æon Flux standards: Trevor Goodchild begins his leadership of Bregna by declaring a regime of radical openness, which he unveils by literally disrobing on live video in front of a vivacious reporter and her floating drone-mounted camera. Later in the same scene, he’ll kill on camera, after the reporter, who turns out to be an assassin, attacks him. Æon and her hapless sidekick, Gildemere, try to thwart Trevor’s newly established rule—what has he done with Clavius, the previous leader?

But the closer one looks, the more the threads fray and unravel: We don’t know why Trevor wants to be in charge, any differences in policy he might instigate (beyond ‘the new openness,’ which we don’t get any of the larger context for), or what motivates Æon to move against him. The plot intentionally lacks, or thoroughly obscures, any sense of stakes. Æon and Trevor seem to be playing an erotic game of catch-and-release as much as politically maneuvering, and Gildemere, who is loyal to Clavius, comes off as an overmatched buffoon throughout, standing in for the viewer’s misdirected efforts to fit the plot into the spy or political-thriller genre.

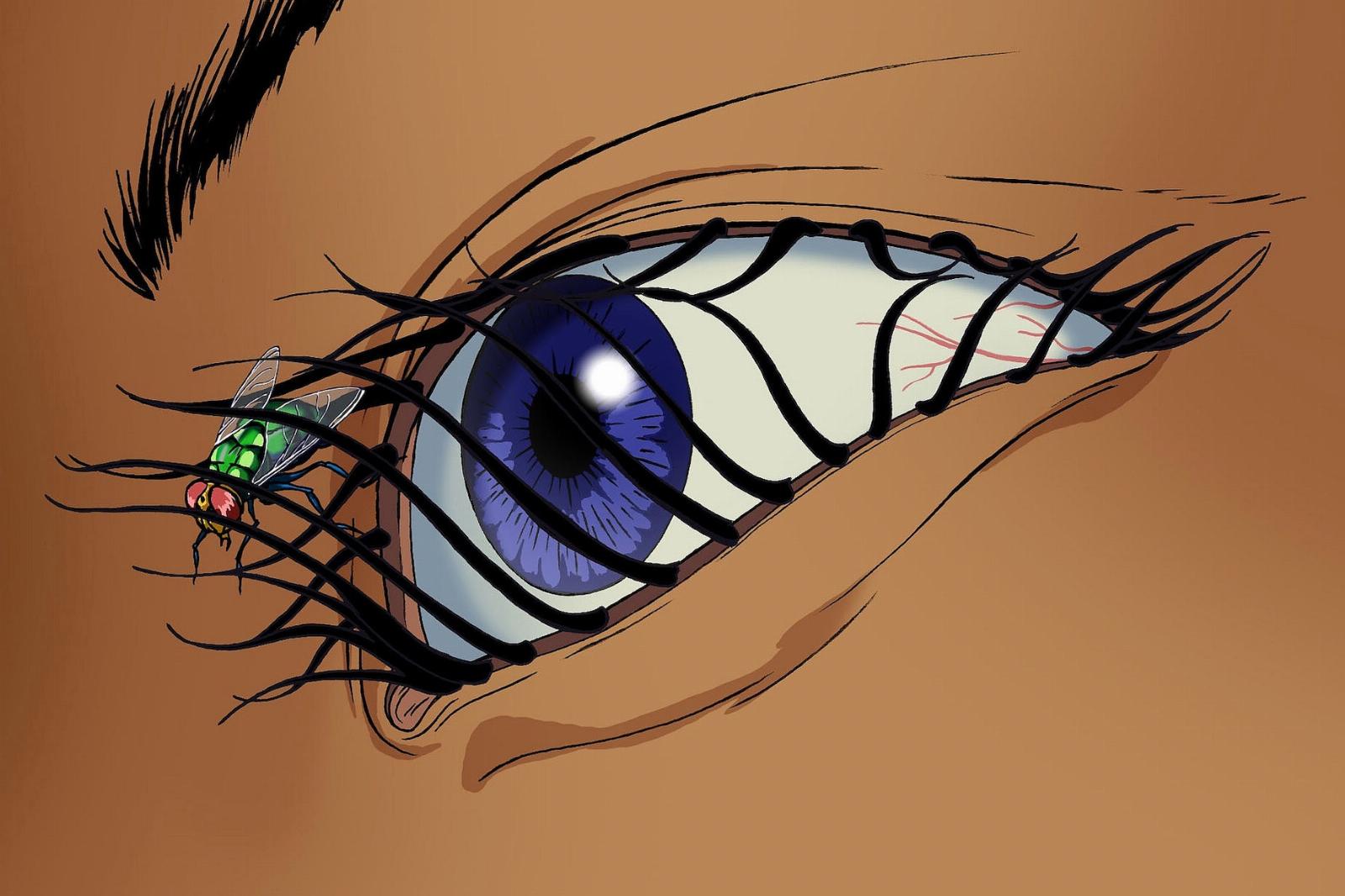

What sticks much better than the slippery plot is the style, the little architectural and technological details, and the visual setpieces: Trevor naked, lithe and triumphant, in front of the buzzing drone; the doubling of the shocked eye of the journalist with the impassive camera lens; the repeated shots of Chung’s serpentine-bodied characters wrapping themselves like bundles of sinew without bones around corners and pillars, furtively watching one another; the security camera that broadcasts Goodchild sleeping, and the Ferris Bueller–esque contraption that slides him secretly under the bed and replaces him with a dummy. The way our look is funneled through camera lenses time and again, the mediated images further distorting the characters’ bodies (at one point, Æon addresses a camera and looks like a bobblehead doll, she’s so foreshortened); the scene in which Æon restrains Trevor and makes him watch while a worshipful security guard rubs and kisses her feet; the way all of the buildings in Bregna are built with large, uncovered windows facing the street, and one another, creating a total urban panopticon in which everyone has the pleasure (duty?) to watch and be watched. Even the combat scenes are distorted by the episode’s fixation on looking; at one point Æon kicks Gildemere off a ladder, and we’re inexplicably jolted from a third-person perspective that allows us to easily track the action to Æon’s perspective as the man bounces off the hard ground below.

The episode opens with a hyper-industrial urban vista, the animated ‘camera’ panning over a dollhouse-style slice of city life: a cart laden with boxes pulls to a stop in front of an elevator, a man drops a box over a ledge—intentionally or not, we never learn. Æon appears to load the box onto the cart, and the man who dropped it over the edge bursts through a door, looking concerned, just as Æon swings out of view. This is storytelling typical of the series’ earlier mini-episodes; who knows what happened, and who really cares? Within seconds, the moving camera makes us realize that we’ve been watching through Trevor’s eyes, as he says: ‘The unobserved state is a fog of probabilities, a window of, and for, error. The watcher observes, the fog collapses, an event resolves. A theory becomes a fact. What is the truth? Tell me if you know, and I will not believe you. Things are never what they seem.’

As we watch and listen to ‘Utopia or Deuteranopia?’ we’re awash in discourse about these sacrosanct notions of surveillance, privacy, transparency—truth and lies, interpretation and reality. But Chung and the rest of the filmmakers state their case immediately, in this first shot of the series: None of these culturally freighted terms are sacred, and everyone is leveraging these ideas for different reasons, to justify themselves, to cloud their true motives, to grasp at power, or just to catch a thrill. In the episode, Trevor will announce ‘Nothing is sacred, nothing is secret,’ and later he’ll just as fervently extol the virtues of privacy, as he’s leading Æon to a secret rendezvous inside the hollowed-out body of Bregna’s former leader: ‘I will give her freedom. True freedom. Freedom from prying eyes and expectations.

A private place. A place of our own.’

It’s a surprisingly 2020s-vibed set of maneuvers, because Æon Flux appreciates that what shoots through and confounds our pieties about privacy, our inconsistent responses to surveillance, is that a lot of us like watching others, and crave being watched. Throughout the episode, and the series, Æon and Trevor are positioned as adversaries, but they’re also addicted, perversely, to orbiting each other in some sort of intensely charged political-erotic-competitive choreography. The more you watch this episode, the more you get pulled into its circularity: We’re watching people watching other people who know that they’re being watched. Their actions are tailored to the presumption that they’re observed, so everything is innately theatrical, even when it’s staged to seem spontaneous. Today, we find ourselves awash in contrived reality TV premises, Twitch streams, OnlyFans bedroom cams, and wholesome family vloggers. Meanwhile, we’re ever navigating impossible negotiations of our privacy, from Ring doorbell cameras and TSA queues to unpredictable location tracking, intrusive search engines, and data brokers endlessly, quietly exchanging our details among themselves. This episode offers an exhaustingly familiar sense of a bleed between private and public, organic and artificial.

So what makes Æon Flux really sing is how its characters inhabit these contradictions with aplomb, a confidence and lack of cognitive dissonance that feels otherworldly. The very real chemistry between Æon and Goodchild is entirely staged, a mannered performance enacted for one another. Meanwhile, narrative beats that feel less managed and planned—as when a handful of armor-clad soldiers run headlong after Æon while she disposes of a body—are styled in a way that makes them feel stilted. The soldiers are moving fast, but unlike Æon and Goodchild, their movements are stiff and jerky, their arms canted at unnatural angles; they look like action figures manipulated by a child’s hands.

When Æon finally gets to the literal bottom of Goodchild’s plan, penetrating his secret bunker inside Clavius’ body, she scoffs: ‘I thought you had an operation here. I thought you were getting some work done. Where is the smoke-filled room? Where are the sleazy characters?’ They exchange some enigmatic barbs, but we don’t learn anything. It’s not so easy, in this science fictional universe: secrecy doesn’t get you any closer to truth, and Æon and Goodchild are just as actorly with one another here, in apparent total privacy, as they are chasing one another through the busy streets.

Ref: slate

MediaDownloader.net -> Free Online Video Downloader, Download Any Video From YouTube, VK, Vimeo, Twitter, Twitch, Tumblr, Tiktok, Telegram, TED, Streamable, Soundcloud, Snapchat, Share, Rumble, Reddit, PuhuTV, Pinterest, Periscope, Ok.ru, MxTakatak, Mixcloud, Mashable, LinkedIn, Likee, Kwai, Izlesene, Instagram, Imgur, IMDB, Ifunny, Gaana, Flickr, Febspot, Facebook, ESPN, Douyin, Dailymotion, Buzzfeed, BluTV, Blogger, Bitchute, Bilibili, Bandcamp, Akıllı, 9GAG